Thomas Erickson

March-April 2024

I close my eyes, as directed.

I am lying on my back. There is a pillow beneath my knees, and another beneath my head. My arms have been carefully positioned on their own supports. I am as comfortable as I have ever been.

Behind my head is a massive machine. It is all white, with rounded edges; it has indicator lights, and subtly designed controls labeled with alien glyphs. The machine is dominated by a circular opening that leads into a cylindrical passage filled with radiance.

Two white-coated attendants have been assisting me. They will leave the room shortly. One attendant tells me that there will be a microphone, and she will be able to hear me if I call. She reminds me that I am to be as still as possible. She asks me if I’m ready to begin. I say yes. The attendants leave.

I am alone with the machine.

The platform I am on twitches, and begins to move slowly. There is humming and vibration, as though thousands of tiny gears are turning, drawing me in. Through my eyelids the muted glow of the ceiling lights shifts, and the light changes as I am drawn into a long tube.

At this point the attendant’s voice tells me that I can open my eyes. There is little to see: a smooth creamy white surface with a subtle pattern arches over and around me, encompassing more and more of my body. The tube, now a tunnel, glows with a soft uniform light. I close my eyes again. I am warm and comfortable and feel no need to speak. I am fully within the machine. The platform ceases to move, slowing so gently that I can’t tell when it comes to rest.

It is otherworldly in here. It reminds me of descriptions of the Tibetan bardo, the intermediate state between one life and another. In the bardo there is a white light, and if you can move into it you can pass out of the world and into nirvana. But I am, as instructed, motionless. To move would disrupt the scan. So I am still. I breath gently. My mind drifts.

I was never that keen on Tibetan Buddhism. I was drawn to Zen. I liked the elegance, the simplicity of Zen. Very minimalist. Tibetan Buddhism is the opposite. It is elaborate, intricate, baroque. There are many different schools, each with its own beliefs and practices and rituals, that have existed for hundreds of years. There are a multitude of deities and lamas and bodhisattvas. There are supernatural beings with mysterious powers that may choose to help you, or not, as you drift in the bardo, awaiting rebirth.

Tibetan Buddhism has a curious affinity for technology. While sutras can be chanted, they can also be written down and placed in prayer wheels that, with each turn of the wheel, produce the same effect as chanting the sutra. More, while prayer wheels may be turned by hand, it is common for them to be designed to be spun by wind, water, heat, or, in modern times, electricity.

The humming has ceased with the platform’s movement, but now another sound begins. It is louder and deeper, a soft thrumming, reminiscent of the chiriring rhythm of frogs on a summer night. But no frogs are these. Again I think of gears, a multitude of them whirling in splendid synchrony. I don’t know what they are doing, but I sense that they are, all together, doing a single thing. I am lofted on the sound. It is like a wordless chant.

The machine I am in is a scanner, and I am undergoing what is called positron emission tomography, or a PET scan. We are attempting to locate cancer cells.

#

My father died of prostate cancer twenty-five years ago. As a consequence, I had been watching for it by getting annual blood tests for PSA, short for prostate-specific antigen, the metric by which prostate cancer is assessed. My PSA was very low, and over the years increased very slowly. I tracked the numbers, and the graph I drew showed that it would not rise to a worrisome level until I was in my 90’s. That was comforting. I was also assured that most older men have detectable levels of PSA, but few die of it. That was comforting too, but I prefer graphs to assurances.

Three years ago, what had been a straight line developed a kink, angling sharply upward. It was still at an officially benign level, but the change in slope was unsettling. A year later, it had jagged upward yet again, passing the level of concern. This triggered an MRI scan, and then a biopsy, culminating in a diagnosis of prostate cancer. After some research and much consultation, I settled on surgery as an approach. While surgery has its perils, and a prostatectomy can have significant side effects, I find that once I have a course of action in place, most of my anxiety vanishes.

The surgery went well, my recovery was smooth, and side effects were minimal. I resumed running, and worked to get my body back in shape. Three months after my surgery my PSA was zero. I did a week of solo hiking in the Sierra Nevada. PSA zero. Later I went on a three week geology field trip in Iceland. PSA zero. It appeared that I was cured, but a year after my surgery the PSA test returned a very low but greater-than-zero score. Having a detectable PSA level when you don’t have a prostate is not good. This triggered a scan, like that I am undergoing now; but it could not detect any cancer. This condition, where you have cancer, but it cannot be located, is called biochemical recurrence, or BCR.

I started a new graph. One possibility was that I had cancer in the ducts that led to the now-removed prostate – this would be good news because this sort of cancer is not malignant. If this were the case the PSA level would increase a bit, but would then, over time, fluctuate up and down: the graph would show a sinusoidal curve. Another possibility is that the graph would become exponential, increasing in an ever-accelerating curve: this means that the cancer has become systemic, spreading throughout the body, lodging, in the case of prostate cancer, in the bones and liver. This is the worst case. A third possibility is that the graph increases in a straight line, indicating what is called local recurrence. This means that cancer has spread beyond the prostate, but not widely. If it can be located, it can be removed, and a cure is possible.

For a year I watched the graph. At some level, I was anxious. It was a like an emotional version of my tinnitus, the high pitched ear ringing that I sometimes notice, but that quickly fades into the background. I notice it if I wake up in the night, or try to pay attention to it, but otherwise not. Every three months I had a blood draw and a PSA test. Every three months, the PSA increased. Every three months, I extended the graph. When the numbers are very small, as mine were, it is difficult to tell the shape of the curve. Sinusoidal, exponential, linear, all begin by going up. As time went on, it became increasingly clear that the line was straight. Not the best case, but not the worse. By the end of the year, the PSA level had doubled, and, according to protocol, it was time for another scan.

So here I am in the scanner.

#

An hour ago I was given a tracer known as PSMA-Gallium-68. PSMA is an engineered molecule that will stick to prostate cancer cells, and the element Gallium, attached to the PSMA, will function as a signal. Gallium-68 is a radioactive for of Gallium: it emits gamma rays, high energy light, which means that it can be detected by cameras.

Gallium-68 is like something out of science fiction. It is produced in a cyclotron, a particle accelerator that smashes atoms into other atoms at tremendous speed. The result, Gallium-68, is unstable: it decays over the course of a few hours, which is why it is ok to have it, a radioactive substance, in the body. When an atom of Gallium-68 decays, it emits a positron, a form of anti-matter. This amazes me. Anti-matter is a rare and mysterious thing in the universe–it is the opposite of the matter that makes up the world we know. In theory, protons have anti-protons; neutrons have anti-neutrons; and electrons have anti-electrons, which is another name for positrons. In fact, anti-particles are scarce. Whenever an anti-particle and its opposite meet, they undergo mutual annihilation, transmuting matter into energy according to Einstein’s famous equation: E = MC2. Fortunately for our universe, anti-matter is exceedingly rare; but just now, there is some inside me.

I am a bit like a comic book scientist who, through mischance or madness, has ingested a potion that is inducing an arcane transformation. By now the PSMA has stuck to whatever was present for it to stick to, with the Gallium-68 coming along for the ride. I am beginning to glow. As the Gallium decays, each positron immediately combines with a nearby electron, and their mutual annihilation produces two gamma rays that fly off in nearly opposite directions. These gamma rays make a line, a spear of high frequency energy that impales each cancer cell to which the tracer is bound. Even a tiny clump of cancer cells binds multiple molecules of the tracer, and shines like a scattering of newborn stars in the vast dark nebula of my body. The machine I am in is like a great telescope: it gathers the faint scintilla of energy, gradually forming an image.

So here I am. I was told the scan would take about twenty minutes, but I do not notice the passage of time. I think of Tibetan mandalas, which are said to be intricate depictions of the universe, created to promote healing and protection. This is not so different. Eventually the sound changes and subsides. A voice over the intercom informs me the scan is done. The table withdraws from the machine, as slowly as it entered, and I return to the world. The attendants help me up and wish me well.

I leave the room, and the building. I return home.

#

When I was young, Richard Brautigan wrote a poem called All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace. He spoke of

a cybernetic forest

filled with pines and electronics

where deer stroll peacefully

past computers

as if they were flowers

with spinning blossoms.

I long imagined Brautigan’s vision of an “cybernetic ecology” to be written in a sardonic tone, or perhaps in a spirit of mischievous paradox. I love forests, and I like technology, but this melding of the two leaves me skeptical. Though perhaps Tibetans, with their whirling prayer wheels spun by wind, water and power, may feel differently about the interplay between technology and nature.

As I’ve grown older, technology has come to seem less of a tool to be used at need, and more of an unseen dimension of environments through which I move and in which I dwell. In the last two years I have found myself within a machine six times. Being within a machine, cocooned in a luculent space, changes one. The scanners have become familiar to me, and have also assumed a degree of individuality. They look and sound and feel different. The luminous thrumming of a PET scan is distinctly different from the loud, buzzing, chirping cacophony of an MRI scan. Each is a nexus of power, one beneficent, the other… well, in theory helpful, but more chaotic in its mien. Yet both share the curious deliberation with which they draw me into them, and extrude me when they are finished. While I would not call it loving grace, there is a lesser sort of grace in their algorithmic gentleness, in the progammed care with which each machine reads my entrails and casts my future.

There is more going on here than machines. There are people too. Nurses prepare patients, injecting them with tracers; attendants usher patients into the room and position them on the platform; others run the scanners and monitor their functioning; and, no doubt, previously, others have tested, calibrated and repaired them as necessary. The scanners, as well, interact with other devices, talking over networks, transmitting their findings to others, likely a combination of humans and computers, that in turn analyze the results and distill them into plans and treatment protocols. While I don’t see the harmonious cybernetic ecology envisioned by Brautigan, the number of participants, their interconnectedness, and the ongoing nature of their interactions is not so different. There is a web of humans and machines, that somehow, together, perform tasks far more complex than any single entity could on its own. The machines are skilled at seeing – they have an almost unimaginable ability to visualize what would otherwise be invisible – and the humans provide knowledge and intelligence to interpret what is made visible. There is no single entity, neither human nor machine, that has a complete picture of what is going on.

This web of humans and machines also spans time. The knowledge that underlies my treatment has a deep history. The discovery and isolation of Gallium dates back to the 19th century, as does that of radioactivity. The technique for generating artificial radioisotopes, like Gallium-68, was created a few decades before my birth. PET scans were invented in 1950’s during my childhood, but were not useful for prostate cancer diagnosis without a radioactive tracer that could bind to cancer cells. PSMA was discovered in the early 21st century as I approached fifty. It took another decade, as I entered my 60’s to find practical ways of producing and binding Gallium-68 to the PSMA tracer, and it is only a few years ago, when I was first diagnosed, that papers appeared urging the widespread adoption of the PSMA tracer. This single thread of knowledge spans a hundred and fifty years, and represents the work of thousands of researchers, and in itself is part of an intricate tapestry of knowledge woven of physics and chemistry and medicine and engineering. It is the magic of the modern age.

#

My scan has come into being. It travels the network, moving from one computer to another. A radiologist interprets the image and writes a nearly impenetrable report, and updates my medical records. In their turn, doctors on my care team view the scan and the report and interpret it in light of my history. There is a cluster of cancer cells where my right seminal vesicle used to be. The vesicle was removed along with my prostate two years ago, but evidently a few cancerous cells evaded the surgery. They lodged in nearby tissue, fertile soil, and slowly began to multiply, visible only in the rising level of PSA.

Although unsettling, it is a good result. It is good because the cancer is local: it has not spread beyond where it started. There are many places prostate cancer tends to go – lymph nodes, the liver, and especially bones – and it is not in any of them. It is good because, now that the cancer is visible, it can be targeted. And it is good because my surgeon pronounces it “very treatable,” with “a high likelihood of a cure.” I appreciate the assurance. I anticipate a plan.

Over the next few weeks, a course of action coalesces. I have an MRI to provide a more detailed image of the cancer and its location within my body. Specialists consult, and agree on a single option: radiation. I will return to the machines.

Had I a choice, I would have opted for surgery. What I like about surgery is that the hard stuff happens first, and then one can focus on recovery. Get the worst over right away, and make a plan to move forward! But the cancer is too diffuse; there is too much of a chance of missing something. When a surgeon agrees that radiation is the right way to go, there is, in my view, no more to be said.

Radiation is more of an unknown. It will destroy portions of cells, in particular the DNA. That scares me. I feel confident in my body, and believe in its ability to heal. But the DNA is what provides the template for healing. It is the cell’s plan for moving forward. The radiation will destroy whatever is in its path. The theory is that by focusing radiation on the cancerous area, the damage to surrounding tissue will be minimized. And also that, because the cancer cells are undergoing uncontrolled division, they are more vulnerable to radiation, and less able to repair themselves than normal cells. But the reality is that there will be some random collateral damage. I don’t like randomness.

#

I am lying on my back. My eyes are closed. There is a pillow beneath my knees, and another beneath my head. My legs are positioned in a sort of cast, intended to ensure that my pelvis is always in the same place and orientation. My arms are crossed on my chest. I am comfortable, and partially draped with a warm blanket.

The machine is behind my head. It bears a familial relationship to the others: it is white, with rounded edges, and lights and screens and controls. It has a large circular opening, but it does not stretch out into a tunnel: it is shorter – my feet stick out of one end and my head out of the other. I get a fleeting image of a cartoon character who somehow ended up wearing a barrel. I don’t know if this machine has a name – its purpose is to preform stereotactic body radiation therapy, acronymized into SBRT. Well, it does have a sort of name: this is machine C. This will be my machine; the work it does is so precise that all my treatments will be done on it, rather than its presumably identical siblings, A, B, D, E, F and G. I like that the machine names are musical notes, and in the key of C.

The attendants make some last adjustments to the machine, and turn to me. My body must be precisely oriented. They tug at the pad I’m lying on. I am not supposed to help them. I try to feel my entire body, to relax muscles, to release tension with my breaths, to sense the gravity pulling me towards the earth. I feel a push here, a pull there. Machine C indicates that they have me aligned: it can see the three small dots that were tattooed across my abdomen last week. The treatment is about to begin. This time, rather than being injected with a tracer that causes the cancer to emit rays of light, the reverse will happen: the map from my earlier scan will be used to direct beams of high-energy photons onto the cancerous area. I am pleased by this symmetry.

The attendants ask if I am ready. I am. They leave the room. The door clicks shut. I am alone with the machine.

I listen. In the background there is the constant hum of the ventilation. Somewhere fans are whirling, round and round. I am below ground in vast warren of rooms, and the building needs to breath. Now another layer of sound begins, a sort of breathy cyclic hum. If I had a better ear, I think I could identify it as a note. This is a scan, producing another image of my body. My body is alive, and every day, every hour, it is different. My bladder, intestines, and other organs change a little in size and orientation and location, and this scan will make this treatment more precise.

I lie still and quiet for a long time. In another room, a team works to align the treatment plan to the new scan. They will project nine beams of photons into my body, each from a different direction, that will converge on the area where the cancer is. The convergence is the easy part; the painstaking work is to adjust the beam geometries so that they will do minimal damage outside the focal point.

As I wait, my mind returns to mandalas. I imagine a mandala of light, being crafted to both protect and destroy. The machine arches over me and around me, and I feel that I am at the center of a mandala, that will, I trust, both heal and protect.

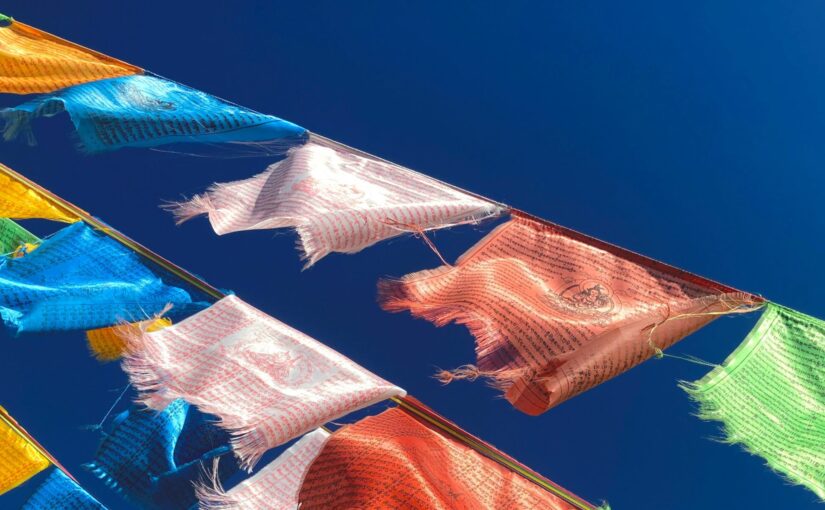

As I wait, I listen to the hum of ventilation and imagine the flow of the air through the room. I picture prayer flags – blue, white, red, green, and yellow – their colors representing the five elements of Tibetan cosmology. Hanging in rows from horizontal lines, they belly out, rippling in the wind. Inscribed with prayers and mantras, they spread peace, compassion, strength and wisdom across the world. As years pass they will fade and fray to tatters, symbolizing impermanence and the cycle of birth and death.

There is a soft click, a twitch of the platform I’m on, and it begins. For a minute there is creaking, as if an old schooner is tacking in the wind, its rigging making small sounds as it accommodates to shifting forces. Then, for a minute or two, there are soft guttural hums as high energy photons stream through me. Then we tack again, and there is more humming. And again. I feel nothing, but I imagine that I am moving, gracefully, through an invisible storm.

Gears and wheels spin. Mandalas are created and dispersed. Within this machine, the last of many, I find a curious similarity between the Tibetan worldview and that of modern science. Not that their content is similar, but that they are too large to fully grasp. They are webs of knowledge and practice woven by countless people, products of deep history. Each, in their own way, offer paths forward to those within their embrace. There are arcane practices to follow. There are rituals and procedures I don’t understand. There are mysterious powers that may help or harm. I find comfort in understanding, but my understanding can only be partial. White-coated acolytes offer guidance. Much must be taken on faith. Prayer flags flap, their edges fraying in the winds.

# # #

Views: 24