*EP#15: The Making of the American Essay, John D. Agata (Graywolf Press, 2016)

Favorites are indicated by ** – there is only one: Blood Burning Moon.

* indicates those that I found something notable in, though I was not keen on them

(*) indicates something previouly read that I still like.

Frankly, I did not care for most of the essays (or, really, most were not essays, but presumably informed or influenced American essayists) in this volume.

This is the 15th volume CT and I have taken up in our essay reading project. Here we return to the type of book we began with — the broadly historical anthology. This differs from previous anthologies we’ve read in that it appears that the editor introduces each piece, something we’ve wished for in the past, especially when we’ve been mystified by why an essay was selected.

Later: Now that we’re farther into it, I’m a little less keen on it. A lot of the material in here are not actually essays: there are short stories, one sermon, a book chapter or two, and some very long pieces (Mark Twain’s A Letter from Earth), none of which strike me as essays. I had hoped for essays, or at least short essay-like pieces… and there are some, but quite a lot is other material. Although his initial introductions were pretty good at situating selections, as the book moves on the introductions are less about the selections, per se, and instead his sort of personal arc through American History. He is also quite fond of experimental work — work that, while it might have raised questions at the time, or contributed to discourse among the literati, is difficult to imagine anyone reading for pleasure or even enlightenment.

Front Matter

To the Reader

A short essay, of a sort, describing a flood that destroyed a town, and revealed ancient mammoth bones with arrowheads embedded in them, pushing back the date at which humans populated the Americas. It goes on to reflect on the accomplishments of North American civilizations, and the fact that they were created (as far as is known) without any precedents or communication with other civilizations. This is held up as an example of creating something from nothing, in counterbalance to the flood which turns something into nothing. The essay ends with an indigenous creation myth about a first creation that was destroyed by a flood, and the way it depicts nothingness by drawing the shapes of the things which have vanished. “What we’re left with, momentarily, is just the shell of what had been there, the physical shape of nothingness, an emblem of the ineffable which we are nevertheless allowed to see and smell and touch.“

Creation

I don’t really find the mythical account, which comprises this entry, that affecting. But to each their own.

The Essays

1630: For My Dear Son, by Anne Bradstreet

In his introduction, Agata introduces Bradstreet as a newly arrived Puritan settler, and as a writer who, in spite of settling 5 towns, having 8 children, and fighting off TB, will “produce more essays, aphorisms, poems and letters than any other English writer of her time — male or female, from either the New World or the Old.“

This particular piece is a series of aphorisms, mostly a sentence or two in length, that strike me as religiously cast, moralistic sayings. Most seemed to me pretty commonplace (a ship with little balast is easily overturned), though I did appreciate one that said, essentially, that you can learn from anyone, either by attending to their positive attributes, or taking warning from their negatives.

1682: The Narrative of the Captivity, by Mary Rowlandson

We skipped this on at my suggestion. It is an account by a settler woman of being kidnapped and spending three months in the wilderness as a captive of Native Americans, before being ransomed. I’d read it when I first purchased the book, before we folded it into this project, and found the piece, aside from some interesting aspects of how the native culture was depicted, to be long, racist, religious, and moralistic. Agata does note, in his introduction to it, that in places the author does express doubts about the war, acknowledge that her captives can be kind (rather at odds with their being servants of Satan), and that she ceases to miss her husband. Apparently this book was a best-seller in the colonies, and possibly its strong religious tone was due, in part, to the urgings of the Puritan leader, Increase Mather.

1741: Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God, by Jonathan Edwards

We skipped this one as well, on Charles’ suggestion, although he acknowledged that it is a famous sermon.

1782: On Snakes, and on the Hummingbird, by J. Hector St John

In the introduction to this essay, the editor notes that the authors’ name is not actually St John, and that he is not actually an English farmer (the essay appears in Letters from an English Farmer) but rather an academically trained French writer. He notes that scholars nowadays are tending to classify the book not as non-fiction, but rather as an epistolary novel. Nevertheless, we have this piece among our essays.

This seems an account of natural history — describing anecdotes and observations of snakes and homing birds — rather than an essay. Part description, part second hand tales that do not seem credible. I’m a little unsure of why this would be in a collection of essays, though I suppose it makes as much sense as the account of Mary Rowlandson’s captivity, or Johnathan Edwards sermon.

Still, I am looking forward more recent writing when the pieces seem more like what I am accustomed to think of as essays. I recall, in thinking of past anthologies, not getting as much out of those from the distant past…

… reading break…

1783: A History of New York, Washington Irving

Seemed interminable. Difficult to see why it was popular.

1836: Nature, Ralph Waldo Emmerson

I had a memory of reading this in the past, and finding it a bit dull and ‘stuffy.’ I find I appreciate it more, although the writing still seems rather stilted, and I do not warm to the tendency to romanticize nature.

One point to make is that this, to me, is the first thing that really feels like an essay. However, I think that has more to do with the remit of this book — on the making of the American essay — than that the essay style was not current. Perhaps it was not current in America, but I feel certain that if I went back and looked I’d find lots of examples from England — Brown, on Dreams, 1790, and probably any number of pieces by Samuel Johnson.

The essay begins with a clear aim, to encourage the reader to form a direct relationship with nature: “The foregoing generations beheld God and nature face to face; we, through their eyes. Why should we not also enjoy an original relation to nature.” . He then goes on to define nature, and to illustrate some of the ways in which such relation might play out, and the advantages that it would bring.

Here is a sample of the writing:

The charming landscape which I saw this morning is indubitably made up of some twenty or thirty farms. Miller owns this field, Locke that, and Manning the woodland beyond. But none of them owns the landscape. There is a property in the horizon which no man has but he whose eye can integrate all the parts, that is, the poet. This is the best part of these men’s farms, yet to this their warranty-deeds give no title.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nature, 131-132

[…]

In the woods, too, a man casts off his years, as the snake his slough, and at what period soever of life is always a child. In the woods is perennial youth. […] In the woods we return to faith and reason.

A bit romantic, but still a nice observation, and one that makes it clear that nature is accessible to anyone who will look. It is easy to imagine readers — and I believe this was quite a popular essay — looking around themselves with new eyes.

And here is more, moving into a more spiritual vein:

Standing on the bare ground,—my head bathed by the blithe air and uplifted into infinite space,—all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eyeball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or parcel of God.

—ibid, p. 132

[…]

The greatest delight which the fields and woods minister is the suggestion of an occult relation between man and the vegetable. I am not alone and unacknowledged. They nod to me, and I to them. The waving of the boughs in the storm is new to me and old. It takes me by surprise, and yet is not unknown. Its effect is like that of a higher thought or a better emotion coming over me, when I deemed I was thinking justly or doing right.

There is quite a lot like this, and it does well enough, but does not personally transport me. There are, however, some very nice descriptive phrases:

- “...this tent of dropping clouds, this striped coat of climates…” p. 133

- “The long slender bars of cloud float like fishes in the sea of crimson light. From the earth, as a shore, I look out into that silent sea.” p. 135

- “The western clouds divided and subdivided themselves into pink flakes modulated with tints of unspeakable softness, and the air had so much life and sweetness that it was a pain to come within doors.” p. 135

1841: Walking, Henry David Thoreau

I wrote about this elsewhere in this blog. As before, I am not that keen on this essay. There are a few nice descriptive passages, but in my later years I have less patience with his condescension towards townfolk, and their ilk.

… reading break…

* 1851: The Whiteness of the Whale, Herman Melville

I can’t say this engaged me, but I was interested to read it. He certainly excels at layering on description after description, and making fine distinctions between similar things. Although prose, it struck me more as poetry.

This is a chapter from Moby Dick, not an essay. It begins with a promise to explain why the author was so appalled by the whiteness of the way, and says, a bit histrionically, that if he does not all the other chapters will be in vain. He begins, with a single sentence that lists dozens of examples, by describing ways in which whiteness adds beauty or value, each clause laying on another example: “and though…, and though…, and though…, ” finally ending with “yet for all these accumulated associations, with whatever is sweet, and honorable, and sublime, there yet lucks an elusive something in the innermost idea of this hue, that strikes more of panic to the soul than that redness which afrights in blood .“

He then, in a new paragraph, evokes the polar bear, and the great white shark, and the white albatross, and speculates on how their whiteness intensifies the terror which they evoke. This is a brief paragraph, but then, oddly, he has two footnotes that occupies more than a page and a half, discussing the bear and the shark and the alabtross. Why did he put it in footnotes?

Here are some samples of his prose, and the way he goes about making his argument:

Nor, in some things, does the common, hereditary experience of all mankind fail to bear witness to the supernaturalism of this hue. It cannot well be doubted, that the one visible quality in the aspect of the dead which most appals the gazer, is the marble pallor lingering there; as if indeed that pallor were as much like the badge of consternation in the other world, as of mortal trepidation here. And from that pallor of the dead, we borrow the expressive hue of the shroud in which we wrap them. Nor even in our superstitions do we fail to throw the same snowy mantle round our phantoms; all ghosts rising in a milk-white fog —Yea, while these terrors seize us, let us add, that even the king of terrors, when personified by the evangelist, rides on his pallid horse.

– Herman Melville, The Whiteness of the Whale, p 205

Here he moves from the pallor of the dead, the the funeral shroud, to ghosts “rising in milk-white fog,” and finally to the end of the world with the king of terrors on his pale horse. It is an evocative and artful train of associations…

[…]

…let him be called from his hammock to view his ship sailing through a midnight sea of milky whiteness – as if from encircling headlands shoals of combed white bears were swimming round him, then he feels a silent, superstitious dread; the shrouded phantom of the whitened waters is horrible to him as a real ghost; in vain the lead assures him he is still off soundings; heart and helm they both go down; he never rests till blue water is under him again.“

Herman Melville, The Whiteness of the Whale, p 207

The image of the white sea is striking, and even more so when the surreal image of it as “shoals of combed white bears” swimming is advanced.

The chapter ends, making its point succinctly and strongly: “And of all these things the Albino Whale was the symbol. Wonder ye then at the firey hunt?“

1854: ???

A Chapter on Autography, Edgar Allan Poe, 1841

This was published in 1841 — I am puzzled by the descrepancy between the date of publication and the editors mini-essays on the dates. This continues as the book progresses.

This is one of those pieces where I wonder why on earth the editor included it. It is a series of paragraphs, each beginning with what purports to be the autograph of a famous person. The paragraph describes the character of writing and the authors… What is the point?

Apparently Poe was interested in handwriting analysis, and believed it could reveal things about the author. But as ChatGPT says: “Poe’s approach mixes serious analysis with a playful tone, and it is important to note that his assessments were often satirical or humorous rather than strictly scientific. He used this platform not only to comment on handwriting but also to offer sharp and sometimes biting commentary on the literary and cultural figures of his day.“

Context (from https://www.americanheritage.com/chapter-autography)

“Early in 1841 Edgar Allan Poe became the first literary editor of the new Graham’s Lady’s and Gentleman’s Magazine . Poe, already a force in American letters, found in Graham’s a superb showcase for his powerful imagination; for the owner and editor, George Rex Graham, was open to any project that would enliven his publication. The average literary magazine of the era was an amalgam of the mediocre, the conventional, and the insipid. Graham set out to revamp this weary field with fresh material, and it is a pretty fair index of his success that in little more than a year’s time the magazine’s subscribers increased from eight to forty thousand. Graham’s recipe was simple enough on the face of it; he gave his readers light essays, originalßction, and verse and spiked it all with sprightly editorial gossip. In so doing he produced that rarity, a magazine equally attractive to men and women, and for a while Graham’s yielded the then enormous annual profit of fifty thousand dollars. Graham’s editorial mixture was ideally suited to Poe’s restless genius. For example, Poe wrote to virtually all the famous American authors of his time, and soon he had assembled enough replies to enable him to embark on a curious project.”

Poe’s essay must have been popular because he went on to write two more…

1858: ???

To Recipient Unknown, Emily Dickenson, 1858

Another piece that I wonder about. This is a letter, or perhaps several letters, rather than an essay, and more poetry than prose. They feel a bit like letters to a loved one, but have a tinge of submissiveness which I don’t care for. And they are a bit difficult to follow…

Reading this did cause me to read more about Dickinson and her life, which seemed constrained and a bit strange. So perhaps all of this is of a piece.

* 1865: The Weather – Does it Sympathize with these Times?, Walt Whitman, 1865

Whitman muses on whether the weather –”the subtle world of air above us and around us” – mirrors the affairs of man, particularly as he writes this during the civil war.

His writing moves between lovely descriptions of the weather and current political events. While I don’t care for personifying nature, he avoids that: connection, if there is any, is suggested by juxtaposition.

On Saturday last, a forenoon like whirling demons, dark, with slanting rain, full of rage; and then the afternoon, so calm, so bathed with flooding splendor from heaven’s most excellent sun, with atmosphere of sweetness; so clear, it show’d the stars, long, long before they were due. As the President came out on the Capitol portico, a curious little white cloud, the only one in that part of the sky, appear’d like a hovering bird, right over him.

– Walt Whitman, The Weather, Does it Sympathize with these Times, p. 229

And again:

The sky, dark blue, the transparent night, the planets, the moderate west wind, the elastic temperature, the unsurpassable miracle of that great star, and the young and swelling moon swimming in the west, suffused the soul. Then I heard, slow and clear, the deliberate notes of a bugle come up out of the silence, sounding so good through the night’s mystery, no hurry, but firm and faithful, floating along, rising, falling leisurely, with here and there a long-drawn note; the bugle, well played, sounding tattoo, in one of the army Hospitals near here, where the wounded (some of them personally so dear to me,) are lying in their cots, and many a sick boy come down to the war from Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, Iowa, and the rest.

– Walt Whitman, The Weather, Does it Sympathize with these Times, p. 230

Very subtly done. It didn’t grab me on the first reading, but now I come to appreciate it.

1874: ???

I am beginning to wonder about these dates and ‘introductions.’ In the beginning and up to about here the dates aligned with the piece… but for 1874…? I can’t find a date for “A Matisse,” but Matisse was only 5 in 1874, and Williams would not be born for nine years.

A Matisse, William Carlos Williams, ?1948?

A brief meditation on a painting, and how it came to be. I spent a little time looking for the painting, but could not identify the one this seems to be about. It has some nice writing:

- “She lay in the sunlight of the man’s easy attention.”

- “So he painted her. The sun had entered his head in the color of sprays of flaming palm leaves.”

1882: ???

And here we have an ‘introduction’ without an essay.

This talks about how various new art movements are critiqued, and the new is reliably castigated as an abandonment of art by the establishment, whether it is painting, poetry, music or writing. This, the introduction says, is the year of the birth of Virginia Woolf, Igor Stravinsky, and Robert Goddard.

1888:

The is the year T.S. Eliott was born, but it is a half a century before the piece was written.

The introduction talks about the effects of the opening of the west, and I think suggests that this is the year that the frontier was proclaimed as having vanished. “As the generation of modernists born this year must learn, when one frontier is closed, you must open up another.

The Dry Salvages, T. S. Eliot, 1941

This is one part of The Waste Land.

It is about water, and rivers, and the sea. It has some resonances, for me, back to “The Whiteness of the Whale.

… reading break…

(*) Of the Coming of John. W. E. B. DuBois

Skipped this one, having read it previously.

…Well, I was going to skip it, but ended up reading it again. As I experienced the first time, it was an engaging read with wonderful and lyrical language. At the same time, it takes an ominous turn when John returns home, and ends with a ghastly depiction of his lynching.

For the purposes of ‘the craft of writing,’ my effort to improve my own writing, I find the first paragraph especially notable.

Carlisle Street runs westward from the centre of Johnstown, across a great black bridge, down a hill and up again, by little shops and meat-markets, past single-storied homes, until suddenly it stops against a wide green lawn. It is a broad, restful place, with two large buildings outlined against the west. When at evening the winds come swelling from the east, and the great pall of the city’s smoke hangs wearily above the valley, then the red west glows like a dreamland down Carlisle Street, and, at the tolling of the supper-bell, throws the passing forms of students in dark silhouette against the sky. Tall and black, they move slowly by, and seem in the sinister light to flit before the city like dim warning ghosts. Perhaps they are; for this is ‘Wells Institute, and these black students have few dealings with the white city below.

–— W. E. B. DuBois, The Coming of John

And if you will notice, night after night, there is one dark form that ever hurries last and late toward the twinkling lights of Swain Hall,—for Jones is never on time.

I like how the traversal of Carlise street is used to set the scene, to describe the layout of Jonestown, and how, in turn, it is given atmosphere, both literally and metaphorically, and finally fleshed out with the silhouettes of students, “dim warning ghosts.’ Then the next paragraph focuses on the protagonist, and the scene is further set so the story can unfold. Masterful writing.

Letters from Earth, Mark Twain

I did not care for this. Twain, in an over-heavy sardonic voice, points out the contradictions and hyprocrisies implicit in the literal interpretation of the Bible as a religious text. He does this, framing it as a series of letters from Satan – temporarily cast out from God’s presence, due to sarcastic remarks – who is spending time on earth, The piece is, perhaps, amusing for a short time, but it is mostly the same tack taken again and again and again, and grows old with repetition.

I did appreciate Twain’s remarking on something that I have always found striking: that the first commandment, ‘Thou shalt have no other gods before me,” presumes that other gods exist, and specifies only that none of the get precedence! This is not quite the monotheistic version of Christianity to which I’m accustomed.

I also appreciated the initial sketch of Satan, particularly early on when he was temporarily banished from God’s presence: “Formerly he had been deported into Space, there being no where else to send him, and had flapped tediously around, there, in the eternal night and arctic chill…“

I believe this piece was published posthumously — I suspect it would have created a lot of outrage during his live… though I am not so curious that I have looked into the matter.

All the Numbers from Numbers,Kenneth Goldsmith,

This piece, by “conceptual writer” Kenneth Goldsmith, makes Twain’s piece seem a sparkling fountain of wit. While no doubt the piece made some sort of point at the time it was published — as did work by DuChamp and Cage and others. While I can imagine the reflections on what it means to be artist provoked by DuChamp, and attention to the ‘silence’ of Cage’s 4’33” – I find it more difficult to see the point in Goldsmith’s lists of numbers and numbered groups. Which is to say I don’t see the point. I can’t imagine anyone actually reading this and coming away with something new.

** Blood Burning Moon, Jean Toomer

Beautiful writing, horrific subject matter. Another piece of writing (resonating with The Coming of John) with lyrical text and a distressing story that descends into a gruesome account of an inter-racial murder and lynching. Here is how it begins:

Up from the skeleton stone walls, up from the rotting floor boards and the solid hand-hewn beams of oak of the pre-war cotton factory, dusk came. Up from the dusk the full moon came. Glowing like a fired pine-knot, it illumined the great door and soft showered the Negro shanties aligned along the single street of factory town. The full moon in the great door was an omen.

Jean Toomer, Blood Burning Moon

I love the writing here. It is like an invocation. The dusk rising from the bones of the town, and the moon rising from the dusk, and the shinning of the moon illuminating the town as an omen…

… reading break…

If I Told Him: A Completed Portrait of Picasso, Gertrude Stein

I really dislike Gertrude Stein. I can’t understand why she is considered a literary figure of any merit. I wonder — half seriously – if she never really recovered from doing research on automatic writing at Harvard (under Hugo Münsterberg and William James).

In spite of my distaste I’ve read through this entire piece looking for something that I find of merit. There is, most obviously, a lot of repetition. Often there is a degree of mirroring of repeated phrases, and play with different senses of the same word, or variants of a word. Critics do comment that she is attempting to use words in the same way that Picasso deconstructed images into repeating shapes seen from different perspectives. But would anyone ever read this for pleasure? Is there a story here? Or some other sort of meaning? I don’t see it.

Some research makes the point that Stein and Picasso knew one another, that Stein was an early patron and supporter of Picasso, and that the essay’s references to “Napoleon” are commentary on Picasso. Some laud Stein for deconstructing language and using it purely for sound and rhythm; others do not think well of it. For instance:

In his critique entitled “Art by Subtraction: A Dissenting Opinion of Gertrude Stein,” B. L. Reid finds most of Stein’s writing to be “unreadable” and of no intellectual value (93). He claims that her poetry is “not for the normal mind” and asserts that it is not worth the time it takes to read it (93). Similarly, Michael Gold in his article “Gertrude Stein: A Literary Idiot” echoes Reid’s claims, and argues that “her works read like the literature of the students of padded cells in Matteawan” further stressing the insanity of Stein’s prose.

– Carly Sitrin, Making Sense: Decoding Gertrude Stein

A review in the New York Times questions Gertrud Stein’s genius:

Gertrude claimed to use words “cubistically,” Leo [Stein, her brother] said, in a manner most people found incomprehensible. “That sounds rather silly,” Picasso observed. “With lines and colors one can make patterns, but if one doesn’t use words according to their meaning, they aren’t words at all.”

— John Richardson, Picasso and Gertrude Stein: Mano a Mano, Tete-a-Tete, 1991

I agree with Leo, and with Picasso.

In a Cafe, Laura Riding Johnson

Another piece of experimental writing. I find it more tolerable because it is stream of conscious, and provides a coherent — if contradictory view — of a recognizable situation.

Everything, even my position, which is not against the wall, is unsatisfactory and pleasing … all this is disgusting; it puts me in a sordid good-humour. This attitude I find to be the only way in which I can defy my own intelligence.

— Laura Riding Johnson, In a Cafe,

I found the most interesting fragment to be this:

I can thus have a great number of points of view, like fingers, and which I can treat as I treat the fingers of my hand, to hold my cup, to tap the table for me and fold themselves away when I do not wish to think.

— Laura Riding Johnson, In a Cafe,

But she does not really do much with it.

Testimony: The United States, Charles Resnikoff

Another experimental piece, although one I find more palatable than the Stein. Apparently Resnikoff worked as a sort of court reported, recording testimony given in various legal disputes, and that he stripped out identifying information and turned it into this… essay, or whatever it is.

I found it mildly interesting, in that it gives some fragmentary impressions of the early 19th Century, and provides glimpses of what life was like in various niches. It is also true, of course, that since these are from court cases it gives only a particular and rather dismal perspective. Perhaps most notable is that way in which the ‘testimony’ — varying incidents that depict violence and death — is presented without passion or judgement.

Not without interest, but not what I look for in my reading.

The Crack Up, F. Scott Fitzgerald

I have read this before. As before, I found it interesting at the start, but it seemed to go on far too long. It became tedious, and somewhat depressing, in a vague way. That is, at least authentic, in the Fitzgerald did struggle with depression or another form of mental illness, ultimately taking his own life about four years after this was written.

I will say little about it, except to reprise a few bits of writing that I appreciate.

The opening is very strong, with its insightful characterization of ‘blows’:

Of course all life is a process of breaking down, but the blows that do the dramatic side of the work— the big sudden blows that come, or seem to come, from outside the ones you remember and blame things on and, in moments of weakness, tell your friends about, don’t show their effect all at once. There is another sort of blow that comes from within-that you don’t fed until its too late to do anything about it, until you realize with finality that in some regard you will never be as good a man again. The first sort of breakage seems to happen quick—the second kind happens almost without your knowing it but is realized suddenly indeed.

– F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Crack Up

And I like this bit:

Before I go on with this short history, let me make a general observation— the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function. One should, for example, be able to see that things are hopeless and yet be determined to make them otherwise.

– F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Crack Up

After this, the essay becomes a recapitulation of his life, before, during and after the crack-up. The middle and latter parts of the essay feel tedious, especially after detailing the ‘crack up’ and its aftermaths, and as the end of the essay it becomes increasingly cynical, as exemplified in ‘the smile:’

And a smile – ah, I would get me a smile. I’m still working on that smile. It is to combine the best qualities of a hotel manager, an experienced old social weasel, a headmaster on visitors’ day, a colored elevator man, a pansy pulling a profile, a producer getting stuff at half its market value, a trained nurse coming on a new job, a body-vender in her first rotogravure, a hopeful extra swept near the camera, a ballet dancer with an infected toe, and of course the great beam of loving kindness common to all those from Washington to Beverly Hills who must exist by virtue of the contorted pan.

– F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Crack Up

… reading break…

(next set to be discussed in July)

Lecture on Nothing, John Cage

I was prepared to dis-like this, and was not disappointed. First, the text is

broken up on the page,

with white space separating words or

phrases in a sentence, so that a page looks like four ragged parallel columns of text,

but you are meant to read all the way across the page.

Similarly, words are ran-domly

hyph-enated, to what end, I do not know.

Annoying.

Nor are the sentences necessarily clear — I suppose they could be regarded as poetic, at times. While some may like this, or find it interesting, I lose patience quickly, and this is a long piece. Well, it seems long, anyway.

I think Cage does have some interesting things to say about form and rhythm, but it’s a chore to extract them from this melange of fragments, and I am not going to make the effort here. So this is a (very) small (partially) saving grace.

In the Fifties, Leonard Michaels

This was not quite my cup of tea, but not wholly without merit. It is a sort of collage of fragments of the author’s life during the fifties. There is not much, as far as I can tell, of an order or structure to it. Just fragment after fragment, most only a sentence of so in length. Most are descriptive, some bizarrely so; a few have a bit of lyricism in them, or work well as sequences of images.

I read literary reviews the way people suck candy.

I worked in a fish packing plant…[…] In a dark corner, away from our line, old Portuguese men slit fish into open flaps, flicking out the bones. I could sce only their eyes and knives. I’d arrive early every morning to dash in and out until the stench became bearable. After work I’d go to bed and pluck fish scales out of my skin.

A lot of young, gifted people I knew in the fifties killed themselves. Only a few of them continue walking around.

I wrote literary essays in the turgid, tumescent manner of darkest Blackmur.

I used to think that someday I would write a fictional version of my stupid life in the fifties.

ibid., pp 503-506

The first three fragments are not adjacent; the last three are. I can’t tell the difference. I liked the image of the old Portuguese men carving up fish, and the reading “literary reviews the way people suck candy.”

This style, a sort of layering of images and anecdotes, is interesting, and gives something of a sense of the time, but I’d prefer it have a structure or order to it.

The Yellow Bus, Lilian Ross

Well. I would love to know why the editor included this piece. The content seems pedestrian; there is no distinctiveness of style or structure. It is the sort of narrative one might expect to find in a high school newspaper or yearbook. Why would someone want to read this, let alone include it in an anthology>

To me it seems like a straightforward, mostly journalistic account of a class of 18 students visiting New York City for the first times. The students have never been to NYC (nor, it sounds like, any large city). They don’t seem to like it much, although their reactions are quite muted. Nothing of note happens: they go to Coney Island, the Statue of Liberty, Central Park, some broadway shoes and take a tour of the city. Then they go home.

… reading break…

Ten Thousand Words a Minute, Norman Mailer

I had looked forward to this piece, having read something else by Mailer on Jackie Kennedy. Sadly, I was quite disappointed. The essay — or article, it is really more journalism than essay – struck me as long and rambling. It reminded a little – as did the earlier piece – of Hunter S. Thompson and gonzo journalism, but without the edgy brilliance: this was turgid prose that was more about Mailer and the milieu of journalism than it was about it’s presumptive topic: the boxing match between Floyd Patterson and Sonny Liston.

There was little in the way of clever turns of phrase, or imaginative descriptions. Telling, the passages I most liked described reporters, rather than fighters, or even the milieu of fighting:

Have any of you never been through the smoking car of an old coach early in the morning when the smokers sleep and the stale air settles into congelations of gloom? Well, that is a little like the scent of Press Headquarters.

…

Every last cigar-smoking fraud of a middle-aged reporter, pale with prison pallor, deep lines in his cheeks, writing daily pietisms for the sheet back home about free enterprise,

Norman Mailer, p. 532; p. 535

ChatGPT says:

The essay, which first appeared in Esquire, covers the 1962 heavyweight title fight between Sonny Liston and Floyd Patterson but extends far beyond the boxing ring to explore broader themes of identity, struggle, and the American psyche. Mailer uses the fight as a backdrop to reflect on his own experiences and societal observations, inserting himself into the narrative in a way that blurs the lines between observer and participant.

– ChatGPT

* The Fight: Patterson vs. Liston, James Baldwin

This, interestingly, covers the same event as Mailer’s essay, and does so, in my view, far more successfully. It seems to me, as with Mailer’s piece, more a piece of journalism than an essay, but it is crisp, coherent, and its length its more suited to its topic.

Perhaps the interesting thing about the topic is that there’s not much to say about the fight itself: The fight ended with a knock-out in the first round, and there was really almost no contest. Instead, if one wanted to write about it, one had to back off and write about the milieu. Baldwin did this successfully, and describes the problem very clearly at the beginning of his piece.

There was something vastly unreal about the entire bit, as though we had all come to Chicago to make various movies and then spent all our time visiting the other fellow’s set—on which no cameras were rolling. Dispatches went out every day, typewriters clattered, phones rang; each day, carloads of journalists invaded the Patterson or Liston camps, hung around until Patterson or Liston appeared; asked lame, inane questions, always the same questions; went away again, back to those telephones and typewriters; and informed a waiting, anxious world, or at least a waiting, anxious editor, what Patterson and Liston had said or done that day. It was insane and desperate, since neither of them ever really did anything. There wasn’t anything for them to do, except train for the fight.

James Baldwin, p. 585

Baldwin did manage to speak with both Patterson and Liston, and his best passages are from these moments. About Patterson

And we watched him jump rope, which he must do according to some music in his head, very beautiful and gleaming and faraway, like a boy saint helplessly dancing and seen through the steaming windows of a storefront church.

James Baldwin, p. 590

This is beautiful.

This piece is also interesting because Baldwin comments, peripherally, on the issue of race, and of being Black in the US at that time. Speaking about Liston:

He is inarticulate in the way we all are when more has happened to us than we know how to express; and inarticulate in a particularly Negro way—he has a long tale to tell which no one wants to hear.

[…]

I felt terribly ambivalent, as many Negroes do these days, since we are all trying to decide, in one way or another, which attitude, in our terrible American dilemma, is the most effective: the disciplined sweetness of Floyd or the outspoken intransigence of Liston.

James Baldwin, p. 594 … 595

… reading break ….

* The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby, Tom Wolfe

Written in the loose stream-of-consciousness style that seems to be characteristic of TW. I didn’t like this as much as the other essay we read by him, but it was somewhat interesting and had occasional good turns of phrase in it. To wit:

It’s like every place else out there: endless scorched boulevards lined with one-story stores, shops, bowling alleys, skaring rinks, tacos drive-ins, all of them shaped not like rectangles bur like trapezoids, from the way the roofs slant up from the back and the plate-glass fronts slant out as if they’re going to pitch forward on the sidewalk and throw up.

— The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby, Tom Wolfe (p. 603)

It offers a tour of the car-customization movement in the late fifties, and situates it in a sort of California-outlaw-teen cultural world. He argues that the customizers have adopted the ’30’s streamline modern approach and applied it to cars (in contrast to Detroit which is applying the rectilinear Mondrian-type style). I found his characterization of teens as ‘slaves to style’ provocative, as was his contrasting their attraction to streamline modern as a sort of Dionysian rebellion against the Mondrian-inflected design world of the present.

Ar thirteen, this kid was being fanatically cool. They all were. They were all wonderful slaves to form. They have created their own style of life, and they are much more authoritarian about enforcing it than are adults. Not only that, but today these kids especially in California have money, which, needless to say, is why all these shoe merchants and guitar sellers and the Ford Motor Company were at a Teen Fair in the first place.

I don’t mind observing that it is this same combination-money plus slavish devotion to form-that accounts for Versailles or St. Mark’s Square. Naturally, most of the artifacts that these kids money-plus-form produce are of a pretty ghastly order. But so was most of the paraphernalia that developed in England during the Regency. I mean, most of it was on the order of starched cravats. A man could walk into Beau Brummel’s house at II A.M., and here would come the butler with a tray of wilted linen. “These were some of our failures,” he confides. But then Brummel comes downstairs wearing one perfect starched cravat. Like one perfect iris, the flower of Mayfair civilization. But the Regency period did see some tremendous formal architecture. And the kids formal society has also brought at least one substantial thing to a formal development of a high order-the customized cars.

— The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby, Tom Wolfe (p. 601)

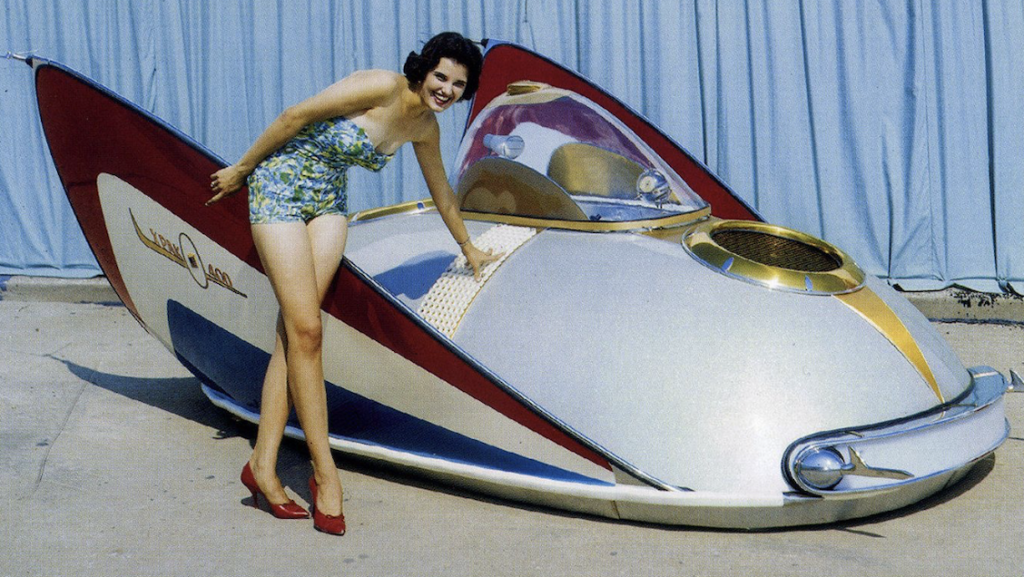

As the article proceeds he describes encounters and discussions with a couple of the leading figures in car customization — George Barris and Ed Roth. Here are a couple of cars created by George Barris:

The streamline modern influence is clearly evident.

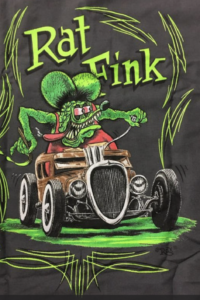

I was interested to learn that Ed Roth was the guy who created (and made a lot of money off of) the Rat-Fink-in-hot-rods pictures. Here is an example of his drawing:

For some reason this was really cool when I was about 9. I have no memory of why.

So that’s the Tom Wolfe essay. A few interesting ideas/perspectives immersed in an overly casually loosely organized essay, with the occasional striking turn of phrase. This is not something I’d recommend to others, but it was interesting to get a sense of a fragment of culture circa 1960, and get more of a sense of Wolfe’s stye

* Frank Sinatra has a Cold, Gay Talese

His 1966 Esquire article on Frank Sinatra, “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold”, is one of the most influential American magazine articles of all time, and a pioneering example of New Journalism and creative nonfiction. With what some have called a brilliant structure and pacing, the article focused not just on Sinatra himself, but also on Talese’s pursuit of his subject. — Wikipedia

I found the content mildly interesting: It was yet another picture of a slice of culture/history that I was only peripherally familiar with, and it provided an interesting characterization of Sinatra, especially of the way in which he surrounded himself with a group of friends and supporters.

The writing did not particularly impress me with its language or imagery, but I was struck by the way in which Talese sketched scenes, often introducing them by anchoring them in time and place, and then interleaved more narrative and descriptives passages. The ‘present’ of the essay is a period of three or four weeks, during which Sinatra begins with a cold, and then recovers and performs well. I’d guess about 75% of the essay is background, narrative, and flashbacks.

… reading break ….

In the Heart of the Heart of the Country, William Gass (1965)

But “In the Heart of the Heart of the Country” is perhaps more indebted to the older tradition of the prose poem for its relatively plotless alternations of preoccupation and mood and its intricate pattern of recurring verbal phrases and imagery (eyes, windows, wings, wires, worms, flies, flying, and spilling—all of which are implicated in a sustained dialectic of the prepositions beyond and in).

—Nasrullah Mambrol, Analysis of ibid.

Not among my favorites. There are lovely (and unlovely) phrases and alliterations and images and passages, but other than evoking an inconstant and despairing moodiness it seems to me lack a point, or even a coherent journey.

Here’s some of the language I like”

- …the railroad the guts the town has straight bright rails that hum when the train is coming

- Down the black street the asphalt crumbles into gravel. … The sidewalk shatters. Dust rises like breath behind the wagons.

- Along the street, delicately teetering, many grandfathers move in a dream

- He steps away slowly, his long tail rhyming with his paws

- drafts cruise like fish through hollow rooms

- in any stinking fog of human beings, in any blooming orchard of machines

- a brightly colored globe of the world with a dent in Poland

Here a stair unfolds toward the street-dark, rickety, and treacherous-and I always feel, as I pass it, that if I just went carefully up and turned the corner at the landing, I would find myself out of the world. But I’ve never had the courage.

The Way to Rainy Mountain, N. Scot Momaday (1969)

In our reading of essay anthologies, this wins the prize for the most frequently anthologized essay. Runners up are “The Crackup,” by F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Hazlitt’s essay on “The Pleasure of Hate.”

… reading break ….

I Remember; Sentence; Signified; Brownstone; Humility; Elliptical (The final half dozen essays)

I didn’t care for any of the last six essays, and did not make notes on them (they are no worse than most of the others, but I was ready to put this book aside). For the record, they are:

- 1 Remember, Joe Brainard

- Sentence, Donald Barthelme

- Signified, Susan Steinberg

- Brownstone, Renata Adler

- Humility, Kathy Acker

- Elliptical, Harryette Mullen

Perhaps single word titles are a red flag?

Views: 14