13 September 2023

In my last entry I was sitting outside in full summer, waiting for my car windshield to be replaced, with my hopes for a beer at the nearby Surly brewery dashed by their continuance of ‘Covid-hours.’ Now, abruptly, after a string of hot dry days, fall is here. Oh, leaves have by and large not started to color, but the light has changed. The air is clear of humid haze, and perhaps, as well, the lowering slant of the sun does something to the color of the light.

Burntside

August was a month of travel, particular for me. Katie and I decamped to Burntside Lodge, a resort near E.ly on the edge of the Boundary Waters. There we overlapped with our friends Kathy and Carolyn, who often visit the lodge several times a year, and had a good time hanging out and being shown around. We also saw Mary G, a friend (and colleague of Katie’s) who has a cabin nearby. It was a nice time, and Carolyn and I had a very nice geology outing, visiting various readouts and her favorite gravel pit. I came home with quite a few large rock specimens. Mostly, basalt, in various stages of alteration. In particular there was some that seemed to show serpentization, with a shiny and slightly greenish hue to it. Very nice.

Yosemite

Because we had shifted our time at Burntside to stay in a more desirable cabin, I had less than 24 hours, once we returned to Minneapolis, to wash my clothes and repack for a trip to Yosemite and other parts of California. But I had already gotten my gear in order, so I did not feel rushed, although I was sorry not to settle back into the home routine with Katie for a few days.

As usual, I left on Sunday and took at early flight to SFO, and drove the 4+ hours to Yosemite. This time I particularly enjoyed watching the terrain change as I crossed the central valley and entered the hills. Reading John McPhee’s “Assembling California” has given me a good context for thinking about the tectonic events that created California: several episodes of oceanic plates, and their accretionary wedges and island arcs, colliding with and suturing to the ever-growing western edge of North America. Some day I would like to get it in my head firmly enough that I can keep track of which terrain I am driving through….

At Yosemite I had a room at the Ahwahnee for three nights. Unlike all my previous experiences, attempts to get a string of five nights in one place in the Valley failed — perhaps bad luck, or perhaps I have never aimed for mid-August. (Normally I would not aim for August, but with the record snowpack this year, everything was late, and I hoped (fruitfully as it turned out) to find spring at the high altitudes.) In any event, the failure led to good things. I had 2-3 more nights booked at Yosemite Valley Lodge, but given that I was going to have to have a ‘moving day’ anyway, I decided that I would move to Lee Vining, outside the east entrance to the park, which is much more convenient to Tuolumne Meadows. But let’s stay in the Valley for a bit.

I had arrived in the Valley simultaneously with the landfall of hurricane Hilary in Southern California. Fortunately the storm moved inland across Arizona and Nevada, and while the east side of the Sierra apparently got some significant rain, the west side was only slightly affected. As a consequence, Monday was a rainy day, with intermittent periods of sun interspersed with light rain showers.

Monday – Veins and aplite on the Snowcreek Ascent

I head out after a hearty breakfast at the Ahwahnee. They are still only doing breakfast buffets, so I was denied my once-customary breakfast of corned beef has, poached eggs, and fruit. But still I ate well. Anyway, I had decided I would just do part of the Valley Loop Trail, and save the long hike to Little Yosemite Valley for Tuesday.

I set out towards Mirror Lake with the idea of going up to the Snow Creek Trail, and perhaps doing a partial ascent of the Valley wall. Last year I took that trail all the way to the top; it was relatively untraveled, and for reasons I couldn’t discern, seemed less of a mindless trudge along switchbacks than the famous Yosemite Falls trail. In any event, I am not planning on a full ascent; I’ve had a slight tinge of a headache in the night, which I attribute to altitude, and so think that an easy first day would be best.

Today it’s a bit rainy, ragged clouds tumbling by overhead releasing the occasional showers; tendrils of mist hang in the air, obscuring the valley walls. As I hike, the light shifts as clouds come and go. I like this, because it throws the landscape into new relief, and I notice things that moments before I was passing unaware.

I enjoy the shapes of the giant, slightly edge-softened granite boulders that loom along the trail. Most are colonized by moss and lichen. Here, a slanted pillar of sunlight falls on a granite boulder, turning its mossy surface emerald green. I pause to look and touch, admiring the tiny spiked leaves of the moss. In her book, “Gathering Moss,” Robin Wall Kimmer writes: “Mosses and other small beings, issue an invitation to dwell for a time right at the limits of ordinary perception.” I look at the spikey green tendrils of moss, wet with water and bright in the light; I notice that they share the space with grey green lichen whose smooth surfaces look ancient and indestructible. I recall how Kimmerer says that if you look closely at a carpet of moss, you can see that it mirrors the structure of the forest, with sturdy stems lofting green branches toward the sun, and moisture dripping through the canopy to sink into the surface.

I have developed a porous halo of gnats. Or of some sort of miniscule flying insect. But it is not a very well-behaved halo. The gnats zig in closely enough to catch my attention before they zag away. A wave of my hand dispels the halo, but it returns in a few moments. At least they do not bite, or even touch down. It could be worse. Nevertheless, I pause to examine the sky. The day is damp and humid, with occasional passages of light rain. Just now the air is clear, but twisted pillars of mist float against the sheer granite walls of the valley. I pause and watch them closely: their tendrils are as motionless as mist in a painting. Likewise, the highest leaves of the trees are utterly still. There is not a breath of breeze. That’s too bad. Movement on high, of leaves or mist, would mean that after a bit of climbing I would reach a breezy region that would dispel my halo.

Reluctantly I deploy my head net to deter the gnats, and continue on to the Snow Creek trail head. Reaching it, I decide to hike up it a bit.

As I climb, I kept an eye on the granite along the way. It’s interesting to watch how it changes a bit in its textures and makeup, even though it is all formed from magma in the same vast magma chamber. As the trail switchbacks up the valley wall it is possible to get a very good idea of the granite. One puzzle is that while much of the granite is as hard as, um, rock, occasional patches that do not appear to differ in composition are falling apart into grus. Here I can pick up a chunk of granite from the trail and squeeze, and the stone will disintegrate into gravel in my fist, falling to the trail in a soft cascade of sound. I play at being Superman for a few minutes, until a solid piece resists my fantasy and leaves my hand bruised. My best guess is that in these places water is seeping through microfractures and altering the granite’s feldspar minerals into clay – but in the damp of the day, I can’t tell if the disintegrating granite is wetter than the rest. Another question for another day.

As I walk a bit farther, I begin to notice the occasional fine-grained pinkish stone among the gray-speckled granite. The part service, in building the trail, stacks up chunks of rock into short walls to slow erosion, and the pink stones really stand out. As I moved higher, I was pleased to notice a vein of pinkish stone in the valley wall; and then, higher still, many veins of different sizes and slightly different compositions. I imagine that after most of the magma had solidified into the batholith, another intrusion occurred forcing its way up, opening a series of fractures that resemble an upside down lightning bolt. I have been reading out veins in igneous rocks, and think that what I’m seeing here is aplite, which is essentially a very fine-grained form of granite, produced from the last watery remnants of a magma chamber. My source says that such late intrusions can either be fine-grained or pergmatic (with large visible crystals). It attributes the difference to whether the magma has de-gassed and lost a lot of the water or not. (I would like to understand why – that’s not at all clear to me). I found examples of both.

On the way back in the valley I notice occasional pieces of very dark stone – I am guessing that it is a diorite, but it is interesting because the crystals within it are tabular, which I’ve not seen before. What could it be?

Tuesday – Little Yosemite Valley

I got up at 5:00 am – 7:00 CT so not an unreasonable hour – and after prepping my hiking gear went down and wrote the foregoing in the lounge while waiting for breakfast to start at 7:00. After a leisurely breakfast, I gathered my gear and drove to Curry Village, and caught the bus to the Happy Isles trailhead. The order for the day was my (usually) annual hike to Little Yosemite Valley.

I saw some nice examples of mosses and lichens <picture> on the way up to the bridge that provides a view of the Merced in its gorge. After that I continued up, keeping an eye peeled for aplite, of which I saw little at first. It was the usual ascent, quite crowded with people. One group in particular made me think of the word “chariveri” – which I think of as loud, high spirited group of chattering people. I have a vague notion that it may be associated with weddings, and another vague notion that it originates from India. These may be incorrect, but they fit very well with the chattering group of young Indian women.

When hiking I usually step to the side to allow groups to pass me, which during an ascent gives me a welcome respite and chance to catch my breath. There were a few groups, typically older couples, who would pause in turn and so we would ‘leap frog’ one another going up the trail. Part way up, at a point where a number of people were resting, an older solo hiker I had noticed asked another group if it was worth it to go to Nevada falls. They were not sure what to say, and In an uncharacteristic moment of boldness, I butted in and said it was a lovely spot to go to. This led to conversation, and his declaration that he would follow me to Nevada falls. I’d not intended to recruit a hiking partner, but I suppose this aligns with the old proverb ‘no good deed goes unpunished.’ We set off, and Scot – as his name turned out to be – was quite chatty. He declared that he was an avid outdoors man and lived in San Diego, but that this was his first time in Yosemite. This led to further conversation about nice place to go, and the resulting well-spaced episodes of conversation were largely pleasant, though I avoided being drawn into a discussions of the folly of the government-funded bullet train between San Diego and San Francisco, or why we are spending so very much money on Ukraine. When we reached the top of Nevada falls, we chatted a bit, and then parted ways.

The top of Nevada Falls was as usual: crowded with people who’d day-hiked up from the valley, and with half-domers and back-packers using as a lunch spot before venturing farther east. There were two things of interest there. One was that – unless I was extraordinarily unobservant last year – the park service has opened a new area on the cliff next to where Nevada Falls spills over. It is an area that is about 10 or 15 feet lower than the top, and there is a crude stairway down to it, and rails along most (though not all) of the sheer dropoff into the falls’ plunge pool. It provides a stunning view almost straight down the falls, and also serves as a nice lunch spot, modulo the predatory chipmunks who, when not posing cutely for tidbits, stalk unwary hikers who fail to guard their packs.

The second element of interest at the top of Nevada Falls were aplite veins in the granite. These had all the characteristics I’d read of – light color, fine grain, and a raised profile indicating increased resistance to erosion. Also of interest were the size of the veins – some were as much as a couple feet in width, and answered the question fo why I’d see surprising large chunks of fine-grained pink rocks! These veins, like at least some of the others I saw yesterday, also exhibited cooling joints perpendicular to the direction of the vein.

After lunching at the top of Nevada Falls, I felt restored and full of energy and like I could hike another ten miles before turning around. That turned out to be a rather ephemeral feeling. I left the the top of Nevada falls, and headed up through the throat of LYV: the trial winds upwards past a knob of granite, and the Merced hums in the background, clearly gathering its energy for the leap over the edge. By the time I’d reached the top of the knob, and begun the gentle descent into LYV next to the still energetic Merced, I was out of steam. I thought I would be doing well to make it to the eastern end of the valley. It was not so bad as that, but my burst of energy had indeed dissipated. I entered LYV, and paused by the Merced which, by that time, has become a placid stream notable only for its remarkable green tint. Sitting alongside that part of the stream is one of my favorite places. <picture> <picture>

I managed to continue farther up the valley to the eastern portion that is recovering from the fire of a decade ago. Recovery continues, and in one portion of the burned area the floor is almost carpeted in pine sapplings doing their best to get a head start on their neighbors. <picture> There are also wildflowers in abundance<picture>, and other plants and forbes that are flourishing on the sunlit floor of the burned out forrest. <picture>

( On the way down I was struck by what a rhythmic activity hiking is. Going downhill, the feet and poles work together. Sometimes, if the descent is shallow and the surface unproblematic, the right pole strikes the ground simultaneously with the left foot. If the slope is bit steeper, the right pole stirkes the ground slightly in advance of the left foot, providing a bit of shock absorption. When the slope is steeper still, or when it is not so steep, but the footing is made uncertain by water or sand or grus (the gravel that granite decays into), the pattern shifts: it loses its regular beat-by-beat rhythm, and takes on something of what I think of as an arachnid character. The poles reach out ahead of the feet, feeling for firm surfaces against which to brace themselves. Often rocks along the side of the path, rather than on the path, serve his purpose; this is one reason I prefer rubber tips on my trekking poles: they can gain a slight purchase – usually all that is needed – on the vertical sides of the rocks, whereas the carbide tips are more likely to go skidding off. Going uphill – periods of which occur even during the 3,000-foot descent of the return – brings a more complex rhythm. Along with synchronized footfalls and pole pushes, is the different but still regular rhythm of breathing and heart beat. It is the heart beat, generally, which persuades me to stop and let others pass, as I catch my breath. )

I hiked into the area until I reached the point I’d made it to last year – visible on the map thanks to the GaiaGPS app. I thought it prudent to turn around here, given my flagging energy, and also it was about the time – between 3:00 and 3:30 – that I had set as much turn around time. Feeling thankful I headed back through a series of spots that for one reason or another have significance for me: the tiny beach alongside the placid emerald Merced; the ‘throat’ leading into LYV; the top of Nevada Falls; the area of cliff with springs that waterfall off of it and support a variety of wildflowers in its nooks; Clark Point; the bridge; and the final descent to the trail head (where, as usual, I walk carefully using by poles as shock absorbers, while the occasional young person sprints by me, running down the final slope.

Now I am back at the hotel. I’ve showered, and have that pleasant full-body-exhaustion that is so nice. The feet and calves ache a bit; hopefully, they will be fine in the morning. I had dinner in the bar, beginning with a large beer that went down wonderfully, and ending with vanilla ice cream. Shortly I expect that I’ll have an excellent night’s sleep.

Wednesday – Tuolumne and Lee Vining

Wednesday was moving day. I had a leisurely breakfast, packed up, and drove across Tioga Road. I had ambitious plans to hike to McCabe Lake. The McCabe Lake destination is because I am trying to find a place I went on a backpacking trip in my early twenties. I was on a trip with Bill Alley, a person I met through the Sierra Club Basic Mountaineering course that I took when I first arrived in California.

(In retrospect, I am a bit surprised that I signed up for the course. It is the sort of thing that is not very characteristic of me — to enter a setting where I had to interact with a bunch of strangers. I do not know what was in my mind, but as I had just arrived in California following college, and new absolutely no one, it was actually a good idea. And it served me well. In addition to learning the basics of hiking and backpacking, I met some people that, at least of a while, I went on some trips with. Bill Alley was the experienced one, and quite senior in that he may actually have ben in his thirties. But he was quite keen on getting out in the wilderness, and quite happy to take newbies along with him, and include them in his backpacking trips and his efforts to become an expert cross-country skier. He taught me to telemark, although I never achieved much proficiency.)

In any event, I had gone on a long trip with Bill, and a couple of other people, in the north-of-Yosemite wilderness, and on the last night before we exited in Tuolomne Meadows, we camped at a lake. The lake was on the north side of a sheer mountain face, and at the time — I can’t recall if it was spring, summer or fall – water was cascading down the east and west sides of the mountain and into the lake. I recall standing at the edge of the lake, and that the sound of the two cascades echoed back and forth and resonated with a deep vibrating chord, slightly reminiscent of the sound of an orchestra tuning. I wanted to find that place again, with or without the resonance.

On the previous year’s trip, I had theorized that the lake in question was Gaylor Lake. I did a hike to it, and when I got there it was entirely obvious that it was not the lake I had in mind. It had a mountain to its north, not to its south, and there was no cascading water at all. This year I looked at the map more carefully, and decided that McCabe Lake might, indeed, be the lake. There was another possibility, but it was such a long hike that I was confident I could not do it as a day hike. Anyway, to cut a long story short, I set out for McCabe lake, but it quickly became evident that i had gotten too late a start, and that I might very well not be able to make it even if I’d gotten quite an early start. So, instead, I slowed down, got diverted by interesting rocks, and had a nice but moderate hike. I finished at a reasonable hour, and drove on to Lee Vining.

In Lee Vining I checked into my lodging, Murphey’s Motel. It was quite basic — the sort of standard 1960’s motel with two stories and all rooms opening to the outside — but had been updated and was scrupulously clean. I showered, and then headed off to ‘the gas station restaurant,’ which my friend Kathy had sent me an article about. This was a restaurant that, as you would expect from the name, was based at an old gas station (a Mobile), but that had made a name for itself as serving good if non-pretentious food, and that had a sort of country-but-countercultural scene going on. I had ribs on that night (and the next night I had their ‘world famous fish tacos’), and the food was as good as advertised, and the scene was interesting and in addition had outside tables with a view of Mono Lake and the mountains beyond.

Thursday – Bennettsville, Boudinage and Ladder Dikes

At breakfast, back at the gas-station-restaurant, I looked over a Geological Guide to Yosemite, and learned about Bennettsville, an abandoned mining ‘town’ (only two buildings) just beyond the eastern border of Yosemite. What was interesting about Bennettsville is that it featured nice exposures of the metamorphic rocks that butt up against the east side of the Yosemite granite plutons, and in particular have beautiful examples of structures referred to as badinage (that’s French for “sausage”). Boudinage describes rock layers that, due to intense heat and pressure, have been squeezed into intermittently bulging shapes, that look, without the need for much imagination, like strings of sausages. In addition, so the book promised, the exposures were glacially polished, so that the boudin’s would be thrown into relief.

So off I went.

The guidance in the book indicated that it was a short walk to the site, and so I dispensed with my pack, including my essentials, my emergency gear, and water. (Note to self: This is not a good idea. Never do this.) The hike in was probably about half an hour, and so I was OK, but by the end of the outing I was sorry not to have water, and quite aware that I could well have had a mishap, injured myself, and wanted to summon help.

The hike in was lovely, and it was interesting to see rock other than the omnipresent granite of Yosemite. As the book explained, when a pluton is emplaced, it brings a lot of heat along with it, which metamorphizes the adjacent rock, and in this case created a circulating ‘geothermal cell,’ that, over a long time, served to extract various metals from the metamorphic rock, and deposit them in veins. Thus, Bennettville, the abandoned silver-mining town.

Anyway, I did find boudines, but never the beautiful ones pictured in the book.

The Bennettville hike was an add-on; my primary goal was to do some hiking in the Tuolmne Meadows area, perhaps for another try at McCabe Lake. But given how much time I’d spent in Bennettville, and also re-evaluating the distance and elevation gain, I decided instead to opt for a return to the Little Devil’s postpile area that I’d visited in spring of 2022.

This turned out to be, given the time and my stamina, a very good choice, as it felt like a challenging hike by the end of it. But it was a good one. I was able to get good looks at mats of orthoclase crystals what had accumulated — perhaps floated to the top? – of the magma chamber, and also at ladder dikes, flowing passages of darker rock that appear to be carrying orthoclase crystals along them (you can see how the crystals are aligned with the dark flow lines.

In the case of both the boudinage at Bennettville, and the ladder dikes at LDP, I was interested to see how, as I moved about the terrains, I could gradually identify more and more examples of each. In textbooks, you only see one or two pictures of a structure, and they are chosen for their clarity. That illustrates the concept well, but it is not as helpful as it could be in aiding the student in identifying structures in the field. Sometimes, in online courses, or in labs, you may be presented with multiple pictures of varying quality, but even there you are encountering them one after the other, and you generally know what one is supposed to be. In contrast, when actually in the field, you move about and catch sight of (possible) examples from varying distances and orientations. Although initially unsure, as you approach more closely or shift your angle of view, you can identify it, and then you also gain more confidence (or not) in your guesses earlier. I suspect that randomness of encountering a new example may also serve to support learning, just as it does in other types of learning.

Beyond Yosemite

Friday – In Search of the Sheeted Dike

Friday morning I rose, had a quick breakfast, and packed up. Today is the first day of a day and a half of driving around to look at geology. Originally the plan had been to recapitulate the trip described by John McPhee in his book Assembling California. However, as the time approached, I recognized that (a) his stops were not very well described, (b) the descriptions were around 30 years out of date, and (c) I didn’t feel comfortable pulling off onto the shoulder on Interstate 80. So I searched more, and found — even better — the website of the Northern California Geological Society, which has a set of field trips that date back to 1954, and, best of all, include a tour of the Smartsville Block led by Elwood Moore, the geologist with whom McPhee was traveling.

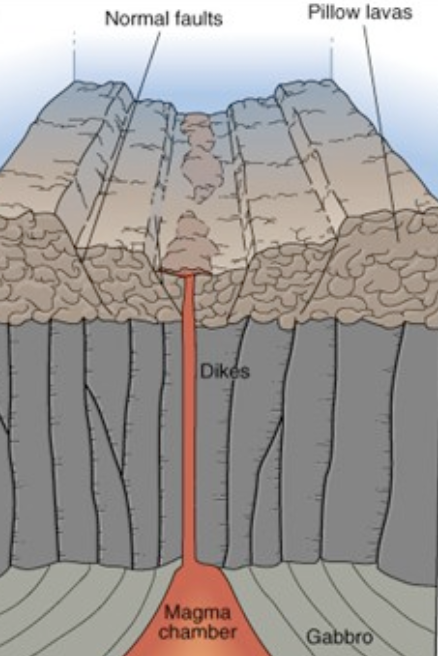

However, as I was starting in Lee Vining, rather than Sacramento, it was clear that the field trip would require far more driving than I wished, and so I decided that I would pare it down to a single stop. An exposed bit of sheeted dike, said to be the best exposure in Western North American and perhaps of all North America. A sheeted dike is a structure that is formed only at mid-ocean rifts… magma works it way up to the surface (that is, the ocean floor) and billows out in pillows; the conduits leading to place of pillowing are the sheeted dikes, so named because each new pulse of magma — occurring, McPhee says, roughly once a century — forces itself up along side an old dike. Thus you have a dike consisting of vertically foliated layers of basalt, with one side of each layer showing a cooling zone.

So, Friday morning, at breakfast, I plugged the coordinates for the sheeted dike exposure that I’d extracted from Moore’s field guide, and discovered to my consternation that they were clearly wrong. I tried adjusting the format of the numbers, tried a few transpositions, but nothing gave me a sensible result. In desperation I went to Google and tried searching for various combinations of words like “sheeted dike,” “smartsville” and “exposure,” and to my surprise found a promising page. It was by a geocaching person who appeared to have created a number of geology related geocaches, including one at Moore’s sheeted dike. I put in those coordinates, and they gave me a sensible destination, and so I set out.

I drove north from Lee Vining up 395 along the east side of the Sierra. It is an easy and spectacular drive. Unlike the southern portion of the drive, if my decades old memories are correct, the northern portion slides right along the base of the mountains: spectacular scenery but without the toll of twists and turns mountains usually extract. I drove up to just south of Reno, and then took a highway across that intersected with I80. I followed I80 through the Sierra and down to Grass Valley and beyond, until I took the turnoff indicated by Google Maps, and made my way along increasingly small roads to the site of the sheeted dike.

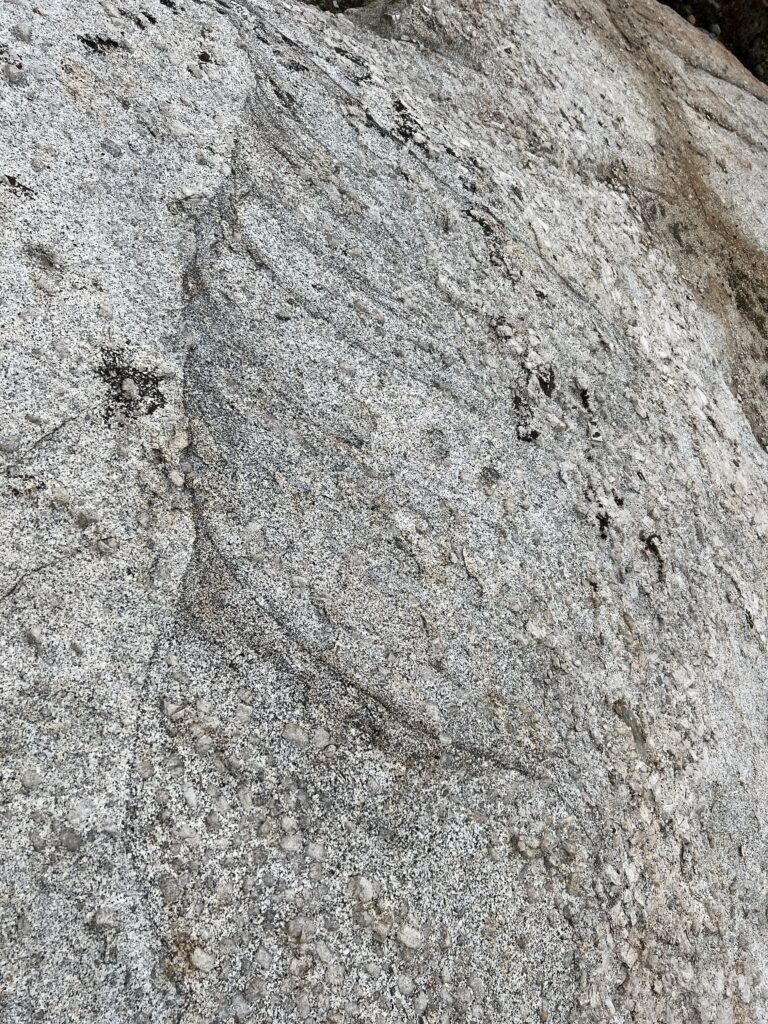

To the untutored eye, or even my somewhat tutored eye, the roadcut in question is unpromising. The only hint that there is something worth seeing is a warning sign – watch for stopped cars – as one approaches. There were no stopped cars, and I turned around in a side road (suggested by the geocaching site) and parked opposite the embankment. I had to search a bit to find anything of note, but finally came to a portion that featured vertically foliated basalt with what I believe were the asymmetric cooling margins that is one of the characteristic indicators of a sheeted dike. The image to the right, while not what I saw, gives a sense of what the ‘sheeting’ looks like in real life.

After finding the sheet dike, I drove to Sacramento where I spent the night. I’d choose what appeared to be a nice new Hilton in a quiet part of town, but its web site failed to mention that it (and my room in particular) was right across the street from the City bus garage, which for some reason required reving up a bus engine at 3:15 am. Despite that incident, I had a reasonable nights sleep, and set out first thing in the morning for the town of Jenner.

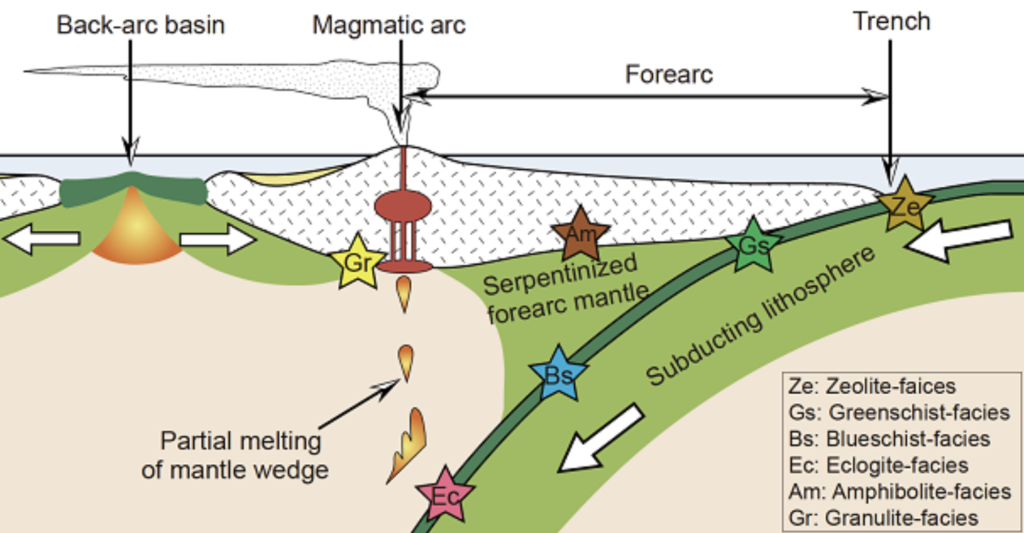

Saturday – Jenner, & RB+CAH

Jenner is a California beach town at the mouth of the Russian river, and was said — in at least one publication I reviewed — to have a particularly beautiful form of blueschist. Blueschist is, as the name suggests, blue, and the Jenner version is also studded with red garnet. My hope was that I could snag a piece to take home with me. More generally, blueschist is a metamorphic rock that is created in the deeper part of subduction zones (deeper than the area where oceanic crust undergoes serpentization). Blueschist is not normally found on the surface, except when there is some sort of disruption to the subduction system — typically, as I understand it, when the trench gets ‘clogged’ by an incoming island arc and the subduction zone gets thrust up onto the surface in what is referred to as an ophiolite.

To cut to the chase, I found Jenner, and I roamed the beach looking for blueschist. The only sample I found would have required a forklift (and a violation of local law) to move, and so I did not get an example. I saw no sign of garnets within the blueschist, though the color of the blueschist itself was enough to make the visit worthwhile. There were also numerous metamorphosed boulders, many of serpentinite; I gathered a few serpentinite pebbles from the beach to bring home.

#

After Jenner, I headed south and joined CAH & RB for a pleasant pizza dinner at their place in San Jose. A lovely end to the day.

Sunday – SF Slickensides with DR, & JH+JG

Sunday morning I rose early and met DR for breakfast at my hotel. He’d offered to chauffeur me around, so I’d returned my rental car the night before. Over breakfast we worked out our trip, at least in part, and headed out.

First stop was a small park in San Francisco, which is notable for have a road cut that displays a massive face of chert that features Slickenslides. Slickenslides are parallel grooves that are created when rock shifts along a fault — they are quite common, I’ve discovered, but to find such a massive example is unusual.

Second stop was Ring Mountain Preserve. It is in Marin County, and is notable (to me, at least) because, like Jenner, it is part of an ophiolite. Ring Mountain is where Lawsonite was discovered – Lawsonite is notable for having a lot of water (about 10% by mass) molecularly incorporated into its structure, and is one of the primary ways water is convert into the mantle. Other minerals include blueschist and serpentinite, and collectively these produce what are called serpentine soils, high in magnesium and other heavy metals, and low in calcium, and thus host a restricted flora that can accommodate the magesium, etc.

After Ring Mountain we returned to the San Francisco area via Tiburon, where we stopped at DRs favorite coffee place, and then returned to the other side of the bay where made various stops at the Praesidio, Fort Funston, and a small Portuguese place for lunch.

After that, DR dropped me at JH & JG’s place. We got caught up on the last couple of years, took a walk, and when out for a nice dinner at an African place. They very nicely drove me back to my hotel.

And that was the trip. I thoroughly enjoyed it, but was happy to go home.

Views: 3