17 March 2024 (posted late)

Our not-much-of-a-winter has passed, notwithstanding a few flakes eddying about in the gusty air today.

I went for a run along Minihaha Creek yesterday. The ice is entirely gone, and the muddy spots from the last snowmelt are dry. We’ve not had much in the way of moisture, either snow or rain, and I’m told 80% of the state is in drought conditions. We shall hope for a moist spring, though not so moist as to bring disaster upon the farmers.

It is interesting to look through the columns of the forest, and see, here and there, a tree hanging onto last year’s leaves.

The phenomenon is called is marcescence, and ecologists have differing theories as to why some species of trees do this. Some suggest that the curled leaves trap a bit of snow, and collectively reserve a bit more water for the tree. Others propose that the dried leaves protect the buds, though, from what I can see, the leaves curl away from the buds, leaving them out there on their own. My favorite theory is that they deter browsing animals, not because of their taste, but because the noisy crunch of a snack of brown leaves may attract predators.

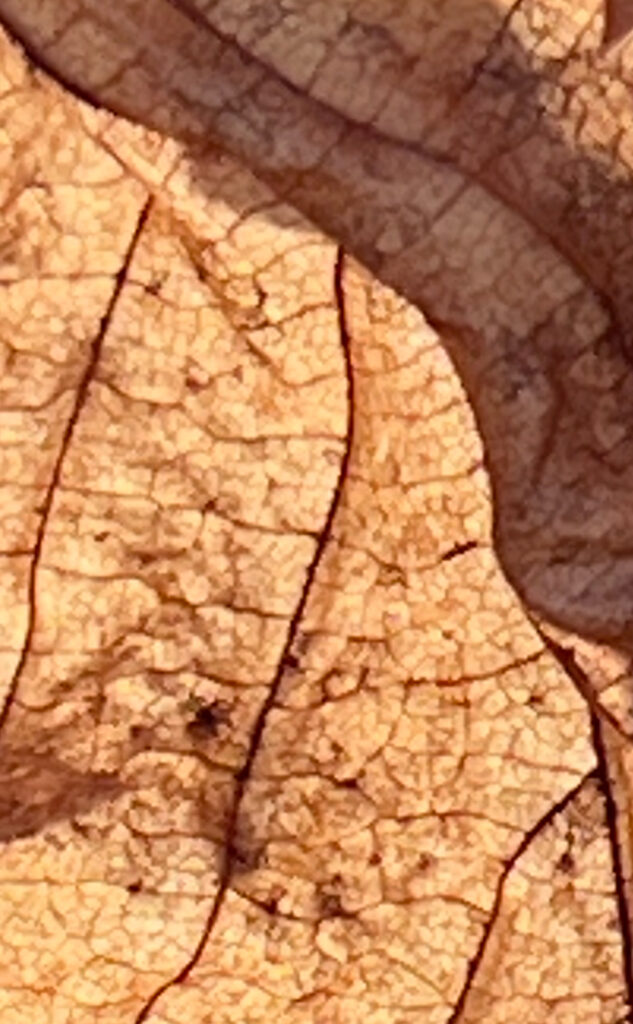

On my run I spent quite a bit of time pausing to look at the old leaves. I find them, up close, quite beautiful. They dry and curl into translucent vaults, their twisted web of veins, like the flanges in a stained glass window, admitting a rutilant light. What would it be like, were I the size of an ant, to saunter beneath them, passing through their arching spaces, tumbled one against another into an Escherian cathedral?

No doubt there is an entire ecosystem within the duff and detritus of woodland floors. Locally, I know, the ecosystems of the “big woods” of central Minnesota, depend upon the presence of a long-lasting layer of debris and duff on the forest floor. That is now being undermined by an invasive species that is not recognized as such — worms. Worms consume the nutrients locked in the duff, interfering with their reabsorption by trees: it is why, for example, many stands of maples no longer turn crimson in the fall: they lack the nutrients to produce the anthocyans responsible for that color. While one might imagine that worms are everywhere, in fact they went extinct in the many northern areas that were subject to glaciation. No doubt they have been slowly moving north in the millennia since the last ice age, but my understanding is that there presence here is more due to human intervention than their no doubt very slow migration.

As time passes, and, hopefully, rain comes, they will begin to melt into the ground. As their substance dissolves, leaving a tracery of stem and vein, they remind me of fossils. Here is a forerunner, having began its dissolution in a puddle.