September 2024 – January 2025

These are notes on “The Light Eaters: How the Unseen World of Plant Intelligence Offers a New Understanding of Life on Earth“, by Zoë Schlanger (read with Rachel). On the positive side, it changed my perspective on ‘plant behavior’ — I knew about some tropisms, but it introduced me to a whole range of ways in which plants sense and respond to their environment and surroundings. Schlanger also writes clearly, and has some lovely turns of phrase, some of which I list below. On the negative side, I think the book is marred by attempts to make it overly dramatic or paradigm-shifting — or perhaps she really buys the claim that plants can be seen as having nervous systems, agency and even consciousness. I don’t think that’s supportable, unless one really wants to broaden (and weaken) the criteria by which we assess such things, and I don’t see the value in that.

Some nicely written turns of phrase

- I savored these tears in the fabric of my day [16]

- I watched the hard beaks of the purple crocuses crack the cold earth like hatched chicks. [16]

- The birds … called wildly, like they were caffeinated. [52]

- I had the dreamlike sense that it had just cunningly frozen in place,,, [53]

- Nature, never a flat plane has always had more folds and faces still hidden from human view. The world is a prism, not a window. Wherever we look we find new refractions. [61]

- “the cloves looked like pearls, all smooth milky curves. … And these cloves, so segmented and perfectly smooth like an orange made of blond wood…?” [p. 126]

Prologue

A beautifully written, lyrical introduction to how the author — a science journalist — became interested in plants. Initially an escape from burnout due to writing about the increasingly dire environmental situation being ushered in by global warming, it turned into a fascination with plants, and the discovery that botany seems on the edge of a revolution in its understanding of plants, particularly with respect to their behavioral/adaptive mechanisms.

Having read the Prologue and Chapter 1:

It looks to be a pleasant and fun read. I hope she will go deeply enough into the science to make it interesting to me.

C1: The Question of Plant Consciousness

- Begins by describing the author’s urge to find something more optimistic to pursue than the increasingly dire findings of climate science. She began to follow papers in botany, and then, two weeks into this new pursuit, discovered that the first genome of a fern — a tiny one called Azoola Ficuloides — had been sequenced. This drew her attention to ferns…

- Ferns alternate generations, with one generation being what we know of as a fern, and the other being a one-cell thick entity on the forest floor that produce motile sperm that can live for an hour. Some ferns are able to produce chemicals that slow the movement of competing species. Ferns are very ancient, and have up to 720 pairs of chromosomes, compared to the 23 humans have.

- Comments on Oliver Sacks’ Oaxaca Journal, and his description of a numinous moment: “when there is a sense of intense reality, almost preternatural reality…” She begins to find descriptions of moments like this scattered throughout the literature on plants, from Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, to the biography of Alexander von Humboldt.

- She became interested in plant behavior, and discovered that early research had been squelched by the debacle of The Secret Life of Plants, published in 1973, which caused scientific funding for research on plant behavior/adapatation to dry up until very recently.

- Plants exhibit behaviors that seem similar to memory, recognition of genetic kin, the ability to sense the sound/vibrations of running water, and the ability to emit chemical compounds of the predators of pests that are attacking the plants

- She talks a bit about her childhood, and her early fascination with plants.

- Terminology and tensios. Discussion of the tensions around discussing whether plants can be said to have senses or intelligence or consciousness. Some scientists are wary of repeating the Secret Life, debacle; others argue that these terms are anthropomorphizing what is going on, and it is simply not helpful; others are less wary.

C2: How Science Changes Its Mind

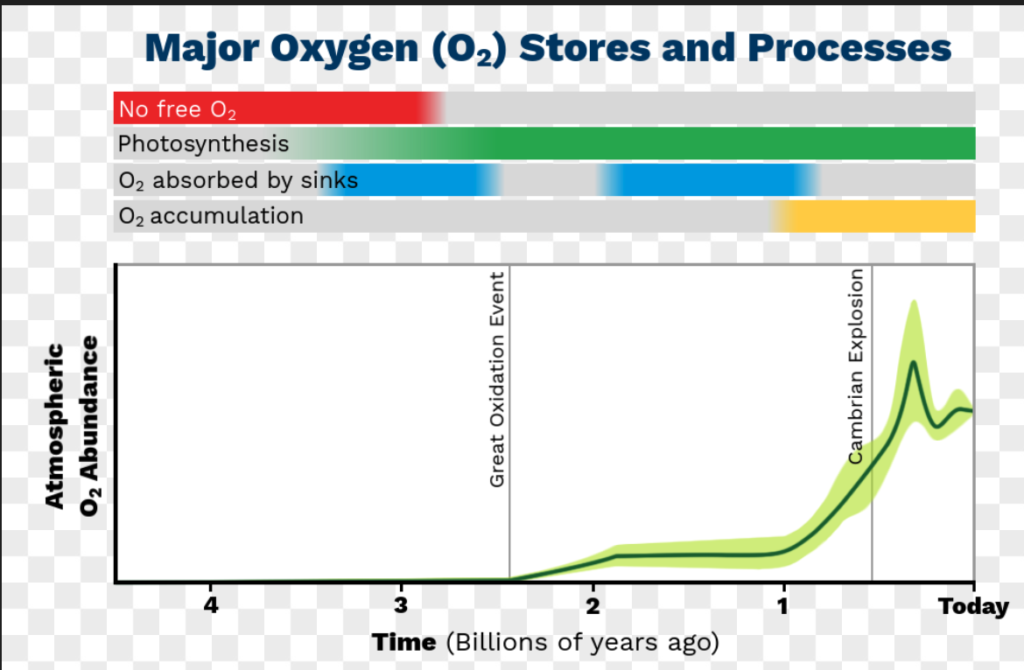

- A brief recap of the evolution of plants, beginning with the incorporation of cyanobacteria into at algal like cell 1.5 Ga. She refers to plants as chimera — I’m not sure if she means more than that their cells contain cyanobacteria…???

- She ties the oxygenation of the atmosphere to the movement of plants onto land 500 Ma — is this correct? I am a little unsure of her timeline re cyanobacteria and oxygenation… below is what I get from ChatGPT, and so she is roughly correct (if we ignore the great oxygenation event and banded iron formations), although there is a lot more to the story…:

- 3 Ga: Cyanobacteria appear. Banded iron formations appear in geological record.

- 2.4 Ga: The great oxygenation event — Oxygen levels rose from almost zero to about 0.02%-0.04% (still very low compared to today).

- 800-540 Ma: Neoproterozoic Oxygenation event — Oxygen levels began to rise more substantially, reaching about 1-10% of present atmospheric levels (PAL), likely due to the evolution of more complex multicellular life.

- 540 Ma: Cambrian explosion: Oxygen to 10-20% PAL. O2 more prevalent in shallow oceans, facilitating development of more complex ecosystems.

- 470 Ma: Plants — bryophytes and liverworts, begin colonizing land

- 430 Ma: Vascular plants appear

- 400 Ma Plants developed true leaves, roots, and woody tissues, leading to the rise of early tree-like plants such as Archaeopteris, which were among the first plants to form forests. (Flowering plants and seeds did not appear until 150 Ma)

- 360 Ma: Carboniferous: O2 reaches 1.5 PAL (35%) due to worldwide forests

- 300 Ma-present: O2 fluctuates but generally decreases and stabilizes at 21%

- She goes on to describe photosynthesis and make the point about how all carbohydrates (and all organic compounds, for that matter) on earth were produced by plants.

- She notes that plants are immobile, and that thus they have to develop a variety of strategies for dealing with predators, reproduction, and forming and maintaining communities.

- She then shifts to Kauai, and biologists involved in trying to save species on the edge of extinction. She notes that it is estimated that 1 or 2 plant seeds made it to Kauai every 1,000 years, and thus it was fertile ground for adaptive radiation, and also that, in the absence of predators, plants lost their normal defense mechanisms (toxins, thorns, etc.) As a consequence, Kauai is losing plant species at a rate of 1-2/year, vs. a normal rate of 1-2/10,000 years.

- Next she turns to human conceptions of plants — especially vis a vis sentience and awareness — and looks at the opinions of philosophers through the ages. Aristotle is the great villain in the demotion of plants of insensate organisms… With the exception of Theophrastus, Aristotle’s successor, who was ignored, plants were disregarded until Darwin began studying them after publication of TOofS, eventually writing four books on aspects of plant ‘behavior.’

- Darwin was particularly taken with the “root cap” of plant roots, noting that it was exquisitely sensitive and could guide the growth of the root, and that it was the only part of a plant which, if removed, would grow back in exactly the same form.

reading break; next discussion Monday, 7 October 2024

C3: The Communicating Plant [Chemical Signaling]

There is a lot here I don’t agree with. The definition of communication seems very loose, and I suspect that simple signaling between plants will ‘inherit’, without any proof, characteristics of human-human communication. For example: “Communication implies a recognition of self.” — I don’t agree. And also “Communication is the formation of threads between individuals.” What does “threads” even mean? And what is meant by “individual?” Very fuzzy.

That is not to say that there are not some very interesting phenomena:

- 1977/1983: David Rhodes, Caterpillars and the Forest. In 1977, David Rhodes, studying the invasion of an experimental forest by a wave of caterpillars discovered that after a couple of years, the caterpillars suddenly began to dies as they fed on the trees because they had started producing toxins their leaves. Furthermore, trees that the caterpillars had not yet reached were also producing these toxins in their leaves. Conclusion: the trees were “communicating” ((or, at least, the affected trees were transmitting signals to unaffected trees that triggered toxin production)). However, although communication via roots had already been established, these trees were too far apart for this to be the explanation: Rhodes posited that communication was due to substances being released into the air.

- Multicellular Organisms. At this point she zooms out and talks about the evolution of multicellular organisms, and what this means: “Each cell in an organism must know who it and what it does.” She goes on to talk of cells “communicating” with one another, and having “awareness.” I don’t care of the way this is expressed, but it does connect with points made in “The Master Builder.”

- Definitions. She defines “communication” as when a signal is sent, received and causes a response. I think this can be simplified to “as signal is sent and causes a response.” I note that she does not require intentionality. So, with this definition, we can say a thermostat ‘communicates.’ OK, but this is such a broad definition that I’m not sure its useful, and I am wary that connotations of more complex forms of communications will be uncritically brought into play where they may not belong.

- Rhodes as ‘ignored pioneer.’ Rhodes published on his research in 1983. Schlanger paints a picture of Rhodes being attacked (“bludgeoned”) by colleagues, though she does not provide references or describe in what ways or for what reasons he was attacked. She does mention, in passing, that he was unable to replicate his results — this is a huge problem, but she skates over it. Eventually, he stopped applying for grants, focused more on teaching, and then died. I suppose this is a nice bit of drama for the book…

- 1983: Baldwin and Schultz published a similar, lab-based finding in 1983, about 6 months after Rhodes. They were able to show, in an experiment with maple seedlings, that damaging the leaf of one seedling would cause other seedlings — whose roots were isolated from one another — to produce protective tannins in their leaves. Unlike Rhodes, Baldwin and Schultz’s careers prospered, even though, unlike Schultz, they used the word “communication” in their papers. To my eye, this discredits Schlanger’s narrative about Rhodes.

- 1`985: Wooten van Hoven observes in 1985 that kudu had suddenly begun dying on ranches in south africa. It appears to be due to (a) their feeding on acacia leaves triggering a build up of toxins in the leaves, and (b) the fact that they were confined on ranches and had no other food sources. Later, investigating why this was not a problem for giraffes, found that they did not graze on most acacias, but rather only on ones that were up-wind from already-damaged trees — and of course they were not confined and had plenty of options.

- 2019/2021: Rick Karban. Sagebrush releases chemicals that can be interpreted by nearby wild tobacco (which can release chemicals that attract predators that prey on caterpillars that are attacking them); also the chemicals released by sagebrush get a stronger response from sagebrush that are more genetically related.

- Aino Kalske, et al. found that goldenrod that live in fairly benign environments release chemicals that can only be interpreted by kin; whereas goldenrod that live in more dangerous environments release chemicals that can be interpreted by goldenrod regardless of degree of kinship. The claim here is that this shows that the chemical communication is beneficial to the sender as well as the receiver… Later: oh, I think the claim is that the signaling benefits other plants rather than just the other parts of the sender. Still, I don’t see that that makes it “communication.” This is imagined as using public or private channels, and having ‘dialects’ and having a clear sense of who is who. — I find this pretty dubious.

- Personalities — bundles of particular ways of acting or responding that differ between individuals. Researchers are looking at these in animals, and now in plants. Karban’s work seems to involve framing this as ‘tolerance for risk.’ Um. Certainly, it is easy to imagine that plants might find different balances between the speed and amount and type of signals they produce, and the expenses that those incur. It would make evolutionary sense for that to vary across a population, just as diversity in other characteristics varies — robustness is good.

C4: Alive to Feeling [Electricity]

- How electricity works in organisms: calcium (etc.) channels and action potentials.

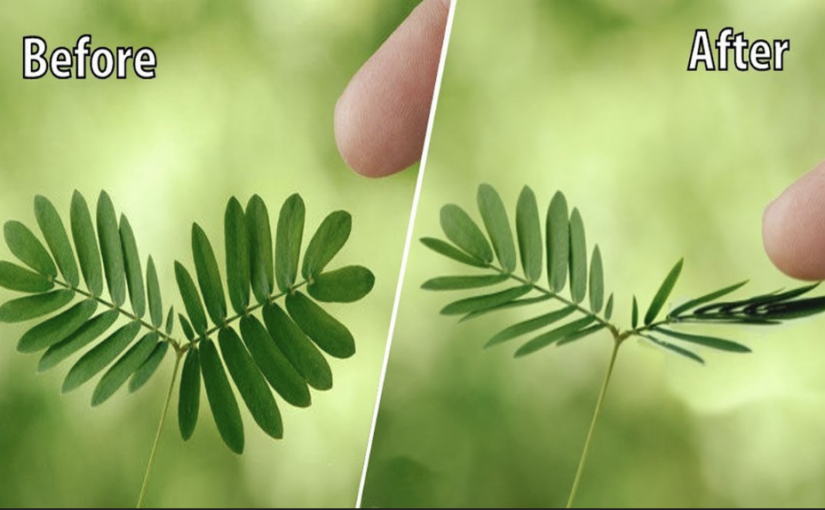

- Anesthesia interfere’s with action potentials — venus flytraps and mimosa can be anesthetized. So can pea plants, which slowly wave their tendrils around over the course of 20 minutes.

- Stoking plants can cause them to stop elongating and instead thicken their stems; other plants may grow more flexible. These responses can be seen as making the plant more resilient to winds and other forms of physical disturbance.

- J.C. Bose (1920’s) showed that plants exhibited electrical responses to various stimuli.

- Barbara Pickard (1993) discovered that plants have calcium channels that enable them to transmit electrical impulses.

- Gilroy and Toyota (). Wound a plant, and a wave of electrical activity propagates across the whole plant. Possibly due to glutamate.

- “Could the whole plant be a brain?” …I don’t think so.

reading break; next discussion 11/04/2024

C5: An Ear to the Ground

- In South American, the flowers of certain vines are structured so that they return the same echo of a pollinating bat regardless of angles. Furthermore, a flower that has not yet released its pollen has a “keel” that reflects the bat’s sonar from multiple directions (not sure if this is in addition to the flower, or if this is just a re-phrasing. One the flower has released its pollen (onto the back of the bat) the keel lowers and the flower becomes inconspicuous to bats.

- Xref Rex Cocroft put guitar pickups on plants to study leafhoppers communicating via vibrations. One day he picked up a rhythmic grating sound — a caterpillar chewing. This led to a collaboration with Heidi Appel to investigate whether the plant ‘notices’ and ‘responds’ to the vibrations created by chewing. They did experiments that established that in response to the sound of caterpillars chewing, the plants — arabdopisis — secreted defensive compounds.

- Acoustic vibrations travel through plant faster than any other signal it can pick up.

- Tomato plants, when predated by caterpillars, secrete a substance that turns the caterpillars cannibalistic.

- It would be very useful in agriculture if sounds could be used to stimulate plants to create their own pesticides.

- Researchers have found that playing sounds can stimulate a plant’s production of vitamin C, its ability to resist a fungal infection, or its ability to deal with drought conditions (not clear why, in these cases). p 108

- Also some flowers can be stimulated to release pollen, or secrete sweeter nectar, in response to a bee’s buzz. In some of these cases, the flower is acting like an amplifier, a sort of resonance speaker.

- Researchers have found that arabdiopsis have tiny hairs on their leaves that are stimulated by sound.

- Roots can also be acoustically sensitive. Pea roots grow towards the sound of running water; they will favor situations where the running water is in a(n accessible tray), but in its absence will grow towards the sound of running water, even though it is within a sealed tube.

- Plants produce clicking noises that are a result of air bubbles in their capillaries bursting. Click rates and patterns are unique to each species, and appear to increase when the plant is under stress or being damaged. …It has been suggested that some vines can use echolocation — where the clicks are producing echos — to locate a surface that they can attach to.

C6: The (Plant) Body Keeps the Score

- Some plants in the Loasaceae family seem to be able to “remember” the frequency of bumble bee visits. They are able to present their pollen at the time they expect a bee to show up. It controls the amount of pollen, and the sweetness of its nectar, to manipulate its pollinators’ behaviors, depending on whether there are many or few.

- Plants in the Loasaceae family have stinging hairs that can inject a painful toxin. The hairs work like hypodermic needles, and their hairs use particular architectures and combinations of minerals to create hairs that will deter their predators.

- “the cloves looked like pearls, all smooth milky curves. … And these cloves, so segmented and perfectly smooth like an orange made of blond wood…?”

- Vernalization: plants that require a certain period of cold before they will produce flowers and fruit.

- Speculation that plant “memory” maybe cellular, like epigenetic.

- Counting: Venus flytraps can count to five, not closing until they’ve ‘counted’ five triggering of their hairs.

- Roger Hangarter: Plants in Motion – A collection of videos of plant movement and growth.

- The Dodder plant parasitizes tomato plants: it’s stem spins around until it encounters a tomato plant stalk, and then coils around the stem: https://www.pbs.org/video/nature-dodder-vine-sniffs-out-its-prey/ The text argues that the Dodder plant is counting as it forms coils, but I don’t see it.

- Meristems — clusters of cells that can adapt to circumstances.

- The chapter ends with what seem to me questionable assertions about the link between behaviors like movement or ‘memory’ and experience. E,g,, “A being that can remember the contours of its world can be said to have experienced it.”Would one argue that glaciers or rivers sense slope because they flow downhill? Or that rocks have memory because their structures contain information about their formation and history?

reading break; next discussion 12/16/2024

C7: Conversations with Animals

I’m becoming increasingly irked with the writing in this book. The author describes some interesting behaviors of plants, but in my view is attributing intelligence and intent to what are really pretty straightforward feedback loops. She started off pretty moderately, but by now the text refers to plants as “speaking,” “warning,” “discussing,” and “proposing.” She also refers to plants ‘relationships’ with animals in terms of “collaborating,” “hiring,” “conscripting,” and “punishing.” It is a bit much.

That gripe aside, she describes a number of interesting symbiotic or mutualistic relationships with insects throughout the chapter:

- Corn plants experiencing predation by a caterpillar release a chemical that attracts the species of wasp that predates on the species of caterpillar that is attacking it. (However, generally, it takes 10 to 14 days for the wasp larva to incapacitate the caterpillar (it is to the larva’s advantage to not kill the caterpillar because they can live off the nutrition it is providing), so that is a lot of time for predation.

- Bumble bees bite mustard plant leaves to stimulate early (by as much as a month) flowering.

- Golden rod can sense the volatiles from near-by gall-forming flies and jump-start their immune systems before the flies make contact. The flies can also detect volatiles from the golden rod indicating that it has increased its immune defenses, and will seek golden rod that is farther away.

- Bittersweet nightshade exudes sticky sap that attracts ants, which feed on both the sap and also the flea beatle larva that predate on the nightshade.

- Acacia trees attract ants by feeding them and providing hollow thorns in which they can nest; when disturbed, the ants defend the tree.

- Legumes that have bacteria-laden nodules that fix nitrogen can cut off oxygen to nodules that are not performing efficiently.

- ~~~ ‘Plants seem to be able to make whatever chemical mixture is necessary…’ — Not really, or the plants that ‘summon’ wasps would instead just produce chemical defenses against their predators.

- Orchids secret pheromones that encourage wasps to try to mate with them, furthering the spread of their pollen. In some cases, different chemicals have to be released in precise ratios.

- Asters and golden rod tend to grow together because, together, their flowers attract more bees.

- James Blande published a paper in which he described plants’ synthesis of chemicals as a language, with a vocabulary and sentences. It is here. Well, he uses “sentence” only once in the paper: “In order to communicate without physical contact, plants require a ‘language’ and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are the ‘words’ in the plants ‘vocabulary’. The quantities and relative proportions of VOCs in the bouquet emitted by plants allow the plant to send complex signals, which using the linguistic analogy could be described as ‘sentences’.“

- Silver birch are predated by weevils, but if they grow in the vicinity of a plant called Labrador tea they absorb the volatiles it releases, which defends it against predation. …The author considers this a “complete sentence,” but I don’t see how that possibly makes sense.

Cannot we also say: ‘When a forest catches on fire, it releases smoke which signals many species of birds and animals to flee, so that when the fire is past the ecosystem can recover more quickly?’

reading break; next discussion 1/7/2025

C8: The Scientist and the Chameleon Vine

Boquila

- Boquila Trifoliata, aka the Chameleon vine, can mimic the leaf color, shape and patterning of plants it grows next to, including non-native plants. In one case, it can even produce a thorn. It is thought — though I saw no evidence – that this reduces predation by allowing it to blend in with the more numerous leaves of its host. (If this is true it should not try to mimic plants that have very tasty leaves.)

- Boquila’s mimicry is good, but often it is not perfect. For example, in cases where the other leaf has a very finely articulated structure, it may produce crude copies.

- In some cases, Boquila may mimic the leaves of a plant that it is not growing on, if the plant has a branch overhanging it — basically, it appears to mimic the leaves that are closest to it. This is not the case for every individual, but about 70% do this — it is not clear if this variation is due to genetics or circumstances.

- On theory is that Boquila is able to visually sense the leaves of plants that are nearby, and thus mimics them; a second theory is that microbes associated with the plants carry genetic information — perhaps micro-RNA – that can serve as a template for the mimicry.

Other plants and related phenomena

- In the early 1900’s the soviet agronomist Vavilov noticed that weeds in crop fields often, over time, evolved to resemble crops. This appears to be true of rye and oats, which seem to have begun as weeds, but evolved to resemble wheat, with its large seeds on stalks. The same is true for barnyard grass, a weed that resembles rice plant seedlings — it’s change has been traced back 1000 years to when rice began to be cultivated. This phenomenon is now known as Vavilovian mimicry. It has been argued that the more modern phenomenon of pesticide resistent plants is just vavlovian mimicry at the biochemical level.

- Plants are, of course, able to detect light, but they can also detect colors of light, to the extent that they can tell if they are being shaded by their own leaves, another plant of their species, or a plant of a different species. Depending on which it is they take differing actions.

- The cells in a plant leaf often lack chloroplasts in their upper most cells, and instead,it is speculated, serve as ocelli, primitive light sensing mechanisms.

- In 2016 a group identified what may be ocelli — spherical microlenses — that would allow microbes to detect light and the direction from which it is coming.

- Mistletoe, like Boquila, can mimic leaf shape, but only that of its host. Boquilla is the only plant that can mimic many different leaf shapes.

- The group that studies Boquilla is also studying a vine called Hydrangia Serratafolia: it sends pink feelers across the forest floor that appear to be able to sense degrees and extents of shade, and use that to assess which plants are large and sturdy enough to serve as a host.

reading break; next discussion xxxI

C9: The Social Life of Plants

- Colony Organisms. Just as bees, termites and other organisms form colonies, where individuals may serve specialized roles and be unable to reproduce, so do some plants. One example is the staghorn fern, which grows in colonies on the trunk of its host, and has some members that never reproduce — disc fronds — and others that do.

- Comments on syncrhonization of brainwaves between collaborating humans. Does not mention Birdwhistle and Hall’s studies of micromovement coordination in the 1950s.

- Plants, at least some, have evolved to live in groups: fields, forests, colonies, clumps.

- In the late 90’s evidence began to mount that plants can distinguish between themselves and others (e.g. their own leaves and roots versus others), and then in the late 00’s Dudley showed that they can also distinguish genetically kin from others. In the case of kin, they behave in a more cooperative manner and share resources; in the case of strangers, they are greedier and try to capture all resources for themselves. This is true of searocket, impatiens, and — as we saw with plant signaling — sagebrush. This is in accord with Hamilton’s rule, which was formulated for animals… (as paraphrased by J. B. Haldane, ‘I would give my life for those of two brothers, or eight cousins.’) Kinship detection appears to happen in various ways: roots picking up on emitted chemicals; leaves sensing the quality of light filtered by other leaves.

- Flowers will invest more energy in producing an attractive floral display if they are growing with nearby kin, taking advantage of the ‘magnet effect’ (where larger displays attract more pollinators).

- When farmers select more vigorous cultivars, it may be that they are working against themselves — in effect selecting ‘sociopathic’ individuals, rather than those that are moderating their competitiveness in the presence of kin.

- In the presence of different species, Asiatic plantains will rush to germinate, and syncrhonize their germination in an attempt, possibly, to shade out their competitors.

- The chapter ends by suggesting that perhaps the role of competition in evolution is not as singularly important as it has been made out to be, and that perhaps cooperation, within and across species is significant — perhaps it is the success of the biome, rather than the species, that is most important. [This seems a bit at odds with the emphasis on kin-favoritism discussed earlier…]

reading break; next discussion 20 January 2025

C10: Inheritance

Well, by this point I am getting a bit exasperated by the author. Interesting examples and phenomena continue to be reported, but I quite dislike the way she pretends to have established farfetched claims in previous chapters. To wit: “In a previous chapter we learned about plant memories, the way plants can recall their own past experiences to make informed choices and change their trajectories.” I would say we did not learn any such thing: I don’t agree that plants have “memories,” that they can “recall their own past,” or “make informed choices.” That is fanciful language that the author tentatively suggested, but now it is trotted out as something “we learned.” Ugh.

I think I was more unhappy with this chapter than previous ones, though I am not sure if it is because the argumentation is worse or if I am just growing impatient with the author’s perspective… but, really, I think it is worse.

- Spigelia genuflexia grows seeds on stalks that bend down and push them into the ground. An interesting behavior, but hardly “maternal” or “parental care.”

- The idea that plants have “agency” is advanced, though a definition of the term is avoided until later. Later it is made explicit: “Agency is an organism’s capacity to assess the conditions it finds itself in, and change itself to suit them.“ I don’t agree that “assessment” is happening, or that there is any sort of reflective process of change. How about: “Adaptivity is an organism’s capacity to respond to the environment it is in by employing the most suitable mechanism from a suite of such mechanisms.”

- There is a critique of a too-strong focus on genetics. I don’t disagree with this per se — it is I think well developed in another book we read, The Master Builder, by Alfonso Arias — but it seems to me that either biologists were exceptionally naive or their position has been grossly exaggerated in this text. Here is sounds like biologists are mystified by the fact that the same plants grow differently in different environments — can this really be true? While ideas about the relative degrees of nature and nurture have certainly been debated, I’m not aware of anyone arguing that nurture (the environment) has no effect.

- Interesting account of the emerald green sea slug, which lives as an animal for the first part of its life, but once it locates a particular type of algae, it ingests the algae, but retains its chlorplasts, which are then able to provide it with sufficient nutrition that it no longer eats.

Elysia chlorotica (common name the eastern emerald elysia) is a small-to-medium-sized species of green sea slug […] that is a member of the clade Sacoglossa, the sap-sucking sea slugs. Some members of this group use chloroplasts from the algae they eat for photosynthesis, a phenomenon known as kleptoplasty. Elysia chlorotica is one species of such “solar-powered sea slugs”. It lives in a subcellular endosymbiotic relationship with chloroplasts of the marine heterokont alga Vaucheria litorea. — Wikipedia

- Discusses invasive species, such as smart weed, from Japan. It characterizes such species as being super adaptive. But it does not address why such plants are not invasive in their native environments. If they are super-adaptive, why did it not enable them to dominate there? It seems to me that ‘super-adaptivity’ would tend to be a negative feedback loop. A plant which is so adapative as to outcompete all its competition should then lose its adaptivity (assuming that such adaptivity takes extra energy) since it is no longer needed… …It is also the case that we know some invasive species (e.g., garlic mustard) appear to lose some of the characteristics that makes them so successful once they have invaded a new ecosystem.

C11: Plant Futures

\

I was not very keen on this final chapter, and made no notes. There was an opening quote from What is Life, by L. Margulis and D. Sagan, which made me interested in reading the book.

Views: 325