December 2024 – April 2025

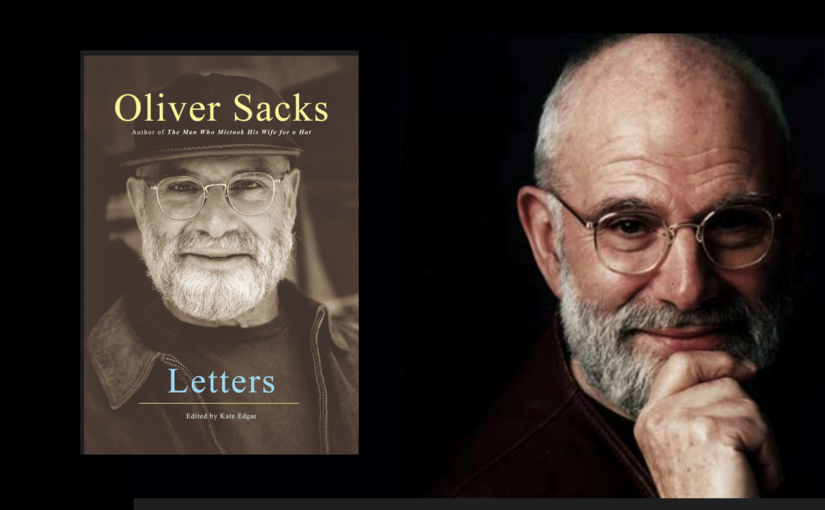

This is book # 16 in the no-longer-very-aptly named Essays Project. Though perhaps, having detoured into the wilds of Shakespeare, a tour of the letters of Sacks, who is a formidable essayist, is steering us back towards the main track. Of course, letters are not essays, but their relative brevity and personal cast, as well as the wide-ranging nature of Sack’s epistles, give them a familial resemblance.

The book is edited by Kate Edgar, Sacks’ assistant and editor of several decades; she also contributes a brief preface which offers her perspective on Sacks’ compulsive writing process. Alas for her brevity; I believe she could offer a lot of insight on Sacks. But perhaps his letters will serve. Onward!

Preface and Editor’s Introduction

Sacks loved correspondence. He felt one ought to reply to letters, immediately if possible. He corresponded with, literally, thousands of people, from school children to Nobel laureates. Sacks took pains to preserve his letters with carbon sets, drafts, or later, photocopies, though by no means does all his correspondence survive. But that part which does runs to about 200,000 pages, or about 70 bankers’ boxes.

Letters were an important way for Sacks to connect to the larger world, possibly a way to do an end-run around what he described as his ‘crippling shyness.’ Certainly they opened him to a vast range of ideas and stimulation; as Edgar says: “Often a serendipitous letter, totally unexpected, would launch him on a new essay or even a book. (p xiii) The letters are also important for understanding Sack’s development, both personally and intellectually.

Edgar offers interesting insights on Sacks’ approach to writing. “[Sacks] had difficulty […] editing his own work. Thus, when one editor or another asked him to clarify something or boil it down, he would simply crank a new piece of paper into his typewriter and start over. Voilà, a new draft. Eventually, the editor would have a pile of drafts, to say nothing of a sheaf of follow-up letters with new footnotes and addenda. It was difficult to choose the best among these, since most versions contained wonderful passages, but each headed in a different direction.” Edgar dealt with this by cutting and pasting among the many draftsand stitching together his various trains of thought.

In the longer term, they developed a more interactive way of working : “Oliver, on the other hand, wanted me actually sitting by his side as he tore each finished page out of the typewriter: “Here! What do you think?” I began referring to this as “combat editing.” I would arrive home after a day with Oliver, exhausted from the nonstop effort of trying to keep up with his restless intellect for eight hours. But it was also exhilarating work, and when he phoned me an hour or two later with new thoughts, I was ready to dive back in. What started for me as a freelance job, occupying a day or two a week, soon became a full-time vocation-and then some.”

Lengthy notes on 1st three chapters

1. A New World: 1960-1962 (27 – 29)

The letters begin with Sacks’ arrival in North America at the age of 27. He had finished four years of medical school and two years of internship, and left England in part to escape the draft, and in part to re-invent himself at a more comfortable distance from his large and opinionated extended family. It is easy to imagine that a significant motivation was his family’s non-acceptance of his homosexuality, but that seems to have only been a small portion of his discontent: his home life, particularly with relation to his parents, was quite a bit more complicated and fraught than was evidence from his biographies. Yet, despite this evident desire to escape, most of his letters are to his parents. I did a double take when he addressed them as “Ma and Pa,” not something I associate with either a Jewish or English upbringing. With regard to his reinvention of himself, we will see that, in addition to continuing in medicine and specializing in neurology, Sacks pursues other interests including motorcycling, weight-lifting, and clandestine sexual encounters.

After an initial period of exploring Canada, and establishing himself in the YMCA in San Francisco, he managed to get a position as an intern in Mt Zion Hospital in San Francisco; he was frustrated because the American medical establishment would not recognize his prior internships in England, and so he had to start afresh in the U.S. While he was initially delighted to get a position at Mt Zion, and spoke well of his bosses — Feinstein and Levin — he grew increasingly discontented with his position and colleagues during this period, until he is able to land a new position in Southern California.

On the personal front, he embarked on a period of trying new things . These included motorcycling (although he had begun this in England I believe), weight lifting and body-building, and various motorcycle tours around North America (trips to southern California; a circuit of most of the U.S., during which he wrote his ‘Truckers’ essay. Other activities he mentions include boar hunting, scuba diving, spear fishing, and camping.

A few other notable things in this section.

- He mentions his love of writing

- He mentions, in a letter to Jonathan Miller, that he has indulged in the purchase of a prism of thallium bromide. Thallium bromide is a superconductor, and is used in detecting gamma rays and other electromagnetic radiation. He reminds Jonathan that he “used to have a strange mystic about such things;” however, as we shall see, his fascination with the elements, and even his totemization of them, is a theme that persists throughput his life. Perhaps this is another indication the he is trying to re-invent himself. However, note, as well, that thallium bromide is “extremely toxic and a cumulative poison which can be absorbed through the skin,” something of which Sacks, in his deep knowledge of chemistry, is no doubt aware. It makes me wonder about his motives, given that a few months later he writes his parents that he is manic depressive and that he has periods of acute sloth and misery.

- He mentions, as well, a neurology conference he attended (paid for by one of his bosses) with many of (at least in hindsight) the ‘greats’ in attendance, including Wilder Penfielld, D. O. Hebb, and Aldous Huxley.

- He also confides to his parents that he thinks he is manic-depressive (something, in later years, that his analyst never agreed with). At one point he refers to “jewel-like spams.”

- He vacillates between an eagerness to see patients and get to know them, and an aversion to them: ‘I should have never become a doctor.’

2. Los Angeles: 1962 – 1965 (29-32)

Sacks is now 29. So far, most of the correspondence — at least that covered in the book — has been with his parents.

He has moved from Mt. Zion hospital in San Francisco where he was an intern to the Neuropsychiatric Institute in Los Angeles, where he is a resident working for Augustus Rose. He will had a tumultuous two years here. On the positive side, it appears he succeeded in impressing his boss and colleagues with his intelligence and drive, but on the negative side his eccentricities — habitual tardiness, slovenliness, large size (due to gaining weight for weight-lifting competitions), consumption of large quantities of hospital food (free to residents, but his degree of consumption is apparently shocking to many). He is reprimanded for the latter, and writes a frosty and indignant letter to his boss taking issue with the reprimand, but also adding, at the end, that “saying ” “a man is not the sum of his minor misdemeanors, but of his best endeavors…” and hoping that he can still count on Rose for recommendations when the time comes to move elsewhere.

He describes writing a paper on hereditary photomyoclonus, and presented it at the big neurological conference which was held in Minneapolis inn 1963 — it was apparently well received. He also mentions becoming interested in neurodegenerative diseases, and imagines writing a major book on the topic, something that has not been done in 50 years. During the next year he apparently continues his work on the topic, and he presents another paper on hereditary myoclonus at the big meeting in Denver — this is apparently a bit of a hit, and he receives job offers and is forgiven by August Rose, who appreciates the publicity.

As in San Francisco, his letters contain mention of many things he is trying out, including photography, camping, fishing, gold panning. scuba diving and spear fishing. He also describes going to a wrestling event with some of his weight-lifter buddies, and how one of the body-builders he’s with, growing impatient at the gates, rips them off, and he and Sacks and a companion lead a crowd on a rampage into the arena. The police are summoned, and arrived, but no one is caught. In another incident, Sacks runs out of gas during a motorcycle trip to southern california, and disassembles his stethoscope to try (unsuccessfully) to siphon gas from parked cars. Also, during this period, Sacks has also amassed enough speeding tickets that he is in danger of having his license suspended, and writes a letter to a Mr. Hobson at the LA DMV pleading for leniency. Clearly Sacks is a rather wild character.

Other notable events

- He gets to know Augusta Bonnard, a friend of his parents, who helps him understand some of the ways the dysfunctionality of his family affected him, and who urges him to undergo analysis, loaning him money to do so.

- He moves in with Mel, a man whom he falls in love with, but who does not return his feelings — or perhaps does, but is too conflicted about his sexuality to act upon it. They part, and Sacks declares he will never live with another person again. This is addressed in the editorial notes (and in his autobiography) but not in these letters.

3. Jenö: 1965 (32)

Sacks is 32, and has arrived in NYC to take a job at Albert Einstein School of Medicine, one of two plumb jobs that were offered to him. He has chosen Einstein because he feels that the people and the institution will be more tolerant of his eccentricities.

However, at the same time, on a trip to Europe for a neurology conference, he met and fell in love with Jenö Vincez. They had a short passionate (amphetamine-fueled) affair while there, and continued it in letters. But by the end of the year it was over — Sack apparently having had a change of heart and ending things.

There are no letters that provide any insight as to what was going on at Einstein, or his relations with the professor who attracted him to Einstein.

Shorter but more systematic notes on the book

At this point in reading events conspired against my prospective note-making. After getting farther on in the book, I found I was getting confused about what happened when, and having difficulty following the arc of Sacks life. So I went back through the book, drawing on the various underlinings and marginalia, and compiled the set of briefer but more systematic chapter by chapter notes provided in this section.

The notes for each chapter include annotations that indicate his age at the time, and the [bolded-bracked text] summarizes the most important developments. Annotations at the end of each chapter summary also signal major events, mostly book publications.

27-29 (1960-62): A New World, p. 3

[Migration; Internship at Mt Zion / Intense travel, exploration, re-invention / motorcycling; weight-lifting; drug use begins?]

Comes to U.S. (initially Canada) to avoid English draft, pursue neurology, and escape his familial constraints and issues. Ends up doing an internship (with which he quickly becomes unhappy) at Mount Zion under Levin and Feinstein in San Francisco. Avid motorcyclist and weight lifter; travels widely around U.S.; pursues clandestine gay relationships.

Milestones:

1960: Moves to San Francisco to take up internship

196x: Self-reinvention & exploration: weight-lifting, motorcycling, drugs

29-32 (1962-65): Los Angeles, p. 49

[Resident @UCLA under Rose. First professional success (Myoclonus) / relationship with Mel E. / addiction]

Moves to UCLA neuropsychiatric institute where he is a resident under August Rose. He reports being slovenly, habitually late, and engaging in off-putting behaviors. Wrote successful paper on hereditary myoclonus; and work, culminating in a triumph in Denver after which he received job offers and was forgiven by Rose for his eccentricities. Has a platonic but sexually charged relationship with roommate Mel Erpelding. Reports pursuing camping, fishing, spear fishing, scuba-diving, etc.. Begins relationships with Marcus Sacks and Agusta Bonnard. 1st recognition of childhood trauma. Bonnard encourages (and later loans him money) to begin seeing a Seymore Bird, a psychotherapist. Moves to NYC/Einstein under Robert Terry.

Milestones:

1962: Moves to UCLA for Residency under August Rose.

1963-5: First professional success with research on hereditary myoclonus.

32 (1965). Jenö, p. 84

[Passionate love affair, mostly by letter / continued addiction; this year he moved to Einstain in NYC, but we hear nothing of that]

A drug-infused passionate up-and-down largely epistolary relationship with Jenö that he appears to end. All the letters in this chapter are to Jenö; I wonder what was going on at Einstein and how he performed (or not).

At a couple of points later in the book, Sacks speaks of a 20 year period of darkness, including a loss of passion for science, as coming to an end around this time, as he leaves California for NYC and begins analysis.

Milestones:

1965: First passionate love affair.

196x: Moves to NYC for plumb job at Einstein.

33-35 (1966-1968). Analysis, p. 110

[In NYC: plumb job but still drug use / analysis with Shengold saves him / Reads Megime, and then writes Migraine; plans more books]

Sacks reports being miserable, with no friends, no interests, and struggling with addiction. It is not clear how things played out at Einstein, but as this period progresses he gets positions @Headache Clinic at the Bronx Hospital and begins seeing patients (maybe with students?) @Beth Abrams. In February of 1967 he reads a 19th C book Megrime, on migraines, and enthralled with it resolves to write his own book, which he does in a burst of creativity during the summer. As he sees patients, he reports that working with patients is more rewardingthan using amphetamines and (says) he kicks the habit. But he is in conflict with his boss Friedman at the headache clinic, who does not want him to proceed with his migraine book. He is also in conflict with Augusta Bonnard who wants him to repay the money she loaned him to take up analysis… Finishing Migraine he has plans for a second book on Parkinsons, a third on asymbolias, and a fourth on the structure of madness.

Milestones:

1966: Begins psychotherapy with Shengold.

196x: Encounters Migraine patients.

36-38 (1969-1971. Coming to Life, p. 148

[@Beth Abrams; Awakenings work begins; More confident re himself & future. Using ergot, but has bad experience. Discovers ferns]

1968 – Use of L-Dopa to treat Parkinsons announced; Sacks applies to FDA and begins his work in spring of 1969. Initially he has great success; but after weeks to months terrible side effects set in. He writes that he has made huge progress with analysis and that Shengold has saved his life many times. And he is beginning to see himself as a clinician who has a feeling for the texture and lives of his patients, and that this sets him apart. Yet he mentions he is still using drugs – specifically ergot – and has a bad experience that leads him to stop. He still seems miserable, and is working all the time to the exclusion of most relationships.

Milestones: 1970: Migraine published. Encounters Parkinson’s patients & uses L-Dopa on them.

38-40 (1971-1973): In the Company of Writers, p. 191

[Auden/Fox/Gunn letters. Friendships and improved lifestyle. Mother’s death. Jonathan Miller saves Awakenings – it is published and attracts notice]

Sacks, who has been getting to know Auden since the poet Orlan Fox introduced them in1969, begins an active correspondence with him. Itounds like he is developing some new adult friends. Migraine has gotten mixed reviews, including a positive one from Auden.

Sacks had written the first 9 case studies for Awakenings in 1969, but had lost them. However he gave a copy to Jonathan Miller, who showed them to an editor who wants to publish them. Sacks writes (or uses an already written) short piece on Awakenings material, that is published in The Listener, and gets a very positive letter from a well-known critic. [The editor of The Listener will later publish a number of the clinical tales which will make up Hat in The London Review of Books.]

Sacks reports swimming regularly and going to hear music, so perhaps his life is getting better. His mother had died, and in the wake of her death he finds the mental clarity to finish Awakenings. Awakenings is published, and although reception is slow, it gets notice and leads to correspondence with both medical people and various editors.

Milestones:

1972: Fired from position at Beth Abrams.

1972: Mother dies.

1973: W. D. Auden dies.

1973: Awakenings published.

41-42 (1974-1975): Astronomer of the Inward, p. 254

[Mixed reviews of Awakenings; intense correspondence w/ Luria; conflict/accusations @Beth Abrams lead to self-destructive behavior]

Awakenings is receiving mixed reviews, and largely negative ones from his colleagues – but he is buoyed by the positive ones. He begins an period of correspondence with Luria (begun after reviewing Luria’s work in 1973, but now becoming very intense. He seems to be continuing to articulate what he is good at, and what his distinctive gifts and contributions are.

Even though he no longer has a position at Beth Abrams, he is somehow still seeing patients there. He has a major conflict with his superiors at Beth Abrams about their use of punishment for patients; they retaliate by accusing him of abusing his patients. This leads to self-destructive behavior: initially he destroys a batch of essays he was writing about them, and later has ‘Leg to Stand On’ accident which he attributes to the conflict as well (in years later writes that he was unconsciously trying to have an accident and cites two other dangerous things he did within a few weeks of that.) He is also corresponding with Bob Rodman, whose wife is dying. Also begins correspondence with Richard Gregory on visual illusions.

Milestones:

1974: Accusations of abuse at Beth Abrams.

1974: Sacks’ Norwegian leg accident.

42-44 (1975-1977): Atavisms, p. 291

[First encounters with Tourette’s patients/community; Luria’s death; Sacks as ‘neurologist-tramp.’ A wide variety of correspondence.]

In this period Sacks first encounters a Tourette’s person and is fascinated. He theorizes a lot about Tourette’s, and intuits an organic basis for it; he comes to realize the syndrome is far more widespread than realized and makes contact with an association of people with Tourette’s. Continues his correspondence with Luria, until Luria’s death in 1977. At one point Sacks remarks that he was closer to Luria than Auden because they had so much to share. In a letter to a student interested in working with him Sacks characterizes himself as a neurologist-tramp – he has no position, but moves around seeing patients at various places including (still) Beth Abrams.

Milestones:

First encounters people with Tourettes.

1977: Luria dies.

42-44 (1978–1979): Coming to Terms, p. 334

[Feelers for adapting Awakenings to other genres. Death of Aunt Len and his misery until he begins writing Leg at Lake Huron. ]

Awakenings has legs, and Sacks is hearing from others interested in adapting it to other genres. His lifelong friend Jonathan Miller draws upon his work for his book, The Body in Question, but does not acknowledge Sacks, who is extremely upset by this and feels that their friendship is at an end (but that does not last).

Sacks writes a last letter to his Aunt, and he is tense and miserable in the wake of her death; he finds relief going to a beautiful country setting at Lake Huron, where his book ‘quickens within him.’ I think this is Leg. During this period he also continues correspondence with Bob Rodman.

Milestones:

1979: Aunt Len dies.

42-44 (1980–1984): Clinical Tales, p. 365

[Object agnosia patient, 1st case study for Hat. Pinter adapatation. Cases published to good reviews in London Review of Books ]

Encounter with a man with object agnosia – will be the first case in Hat. Continues a wide correspondence. Receives Harold Pinter sends him a ms of A Kind of Alaska, based on Awakenings. NYRB wants to do a profile of Sacks, but he refuses when he finds that they will insist on including his homosexuality. Sacks has moved to a small house on City Island, and describes entertaining friends there. Mary-Kay Wilmers, who long-ago published Sacks in The Listener, has co-founded The London Review of Books, and publishes several of Sacks’ clinical accounts between 1981-1983, including 1983: Hat piece (1st chapter) published in London Review of Books.

Milestones:

198x: Some of his clinical accounts published in London Review of Books.

1984: A Leg to Stand On published.

52-55 (1985-1988): Going Deeper, p. 410

[‘Hat’ makes Sacks a celebrity. Develops interests in deafness & autism. S in dialog w/ literary & scientific elite, but also depressed & bored.]

Kate Edgar becomes Sacks’ ‘assistant,’ starting as a typist for ‘Leg.’ He is also writing the pieces for Hat, and many of them are being published in the NYRB and other high profile places; ‘Hat,’ is published in 1985, and becomes a NYT bestseller, but Sacks feels it is shallow. The success of ‘Hat’ deluges him with calls and correspondence, which becomes a trial to answer. But this correspondence also includes elite members of the scientific and literary establishments: Richard Gregory, Francis Crick, Humphrey Osmond, and Susan Sontag.

It is also in this period that he first develops an interest in Deafness, initially in the summer of 1985, and then, in 1988, is visiting Gauladet and developing an understanding of deaf culture, albeit mostly too late to fully inform Seeing Voices which will be published in 1989.

At the same time, during this period, he complains of depression and boredom, mentioning that he has not experienced ecstasy of mind since 1982. He comments that his attachment/love for patients has declined, and dates that to 1979, “coincidentally” when he gave up on trying to achieve an intimate relationship.

Milestones:

1985: Kate Edgar becomes his assistant.

1983: Develops interest in deafness.

1985: Hat published. `

Meets Steven Wiltshire, autistic artist.

56-62 (1989-1995): Adaptations, p. 458

[Edelman / neural Darwinism as explaining adaptive of his patients. Seeing Voices provokes discussion; correspondence with many]]

Meets Gerard Edelman and strikes up correspondence about neural Darwinism – he feels this explains that great degree of adaptivity he has seen in his patients. Quotes Keynes: “The difficulty lies, not in the new ideas, but in escaping from the old ones…”

Seeing Voices is published, and provokes a lot of correspondence, both with psychologists, but also with members of the deaf community who believe he should focus more on culture.

His interest in autism increases and Isabel Rapin serves as a guide; he flies to Colorado to meet Temple Grandin.

Correspondence with Jerome Brunner, Peter Weir, Robin Williams, Stephen Jay Gould, and Daniel Dennett.

An exchange of letters with Peter Friel, a playwright, where Sacks firmly but politely asks for Friel to acknowledge him with regard to his play Molly Sweeny.

Milestones:

1989: Seeing Voices published.

1990: The movie Awakenings is released.

1990: Father dies.

1995: An Anthropologist on Mars published.

63–70 (1995–2003): Syzygy, p. 523

[Sacks is now quite famous and complains, in a letter, of being pestered by publishers and agents. During this period his first non-neurological books are published. In a letter he notes that he still is lured by dangerous thoughts and behaviors. ]

Sacks receives a letter from the author of a book on her experience of being bipolar and returns to his speculations about whether he is bipolar, and to the period he previously called “the tunnel.’ He then says that he has moved into a more equable state in the last fourteen years (age 49, circa 1981) but one that lacks the intense affects in either direction, but also the flashes of inspiration. (I would say that 1981 is around the period where he is transitioning from the buzz/aftermath of Awakenings, and beginning to publish the clinical tales that will contribute to Hat and future books).

Just two weeks after expressing anxiety and boredom with his book ms. Island of the Colorblind, he is thanking Stephen Jay Gould for reading the proofs and alleviating his concerns.

In correspondence with a journalist Sacks characterizes himself as something of a risk-taker: sometimes out of carelessness, sometimes out of courageousness, sometimes as just part of the job. In correspondence with Jonathan Cole he muses about gathering non-neurological, more biographical pieces into a book. He also mentions that he doesn’t want publishers and agents breathing down his neck — clearly at this point he has become a sought-after author.

On page 542 he writes about his feeling about the periodic table as a magical map or secret garden or landscape of his dreams; he also suggests that it was his transition from studying classics to studying science that killed his love for it as an adolescent and that he did not recapture his delight for it until he got out of school.

He continues to correspond with literary and scientific elite: Freeman Dyson, Roald Hoffman, Richard Gregory, Stephen Jay Gould, Howard Gardener, and Peter Singer.

He comments that he still faces very real demons — “the thoughts, the behaviours, the very real dangers that still lure me in his [Shengold’s] absence. “

Milestones:

1997: Island of the Colorblind published.

2000: Oaxaca trip.

2001: Uncle Tungsten published.

2002: Oaxaca Journal Published.

2002: Stephan Jay Gould dies.

70–73 (2003–2006): Snapshots, p. 584

[Nothing published during this three year period. 2004 “sad and painful” due to deaths of many friends: Gunn, Sontag, Crick .]

Nothing published during this period… why? Well, it is a shorter period, and he does remark that 2004 was a “sad and painful year” with deaths of many friends, including Thom Gunn, Susan Sontag and Frances Crick. In a 2005 letter he says that he is writing a series of essays (that will become Musicophilia).

Sacks writes that he got scared off the subject of consciousness in 1992 and turned to chemistry and botany for a decade. Later he writes that he was appalled at the size of the problem and the number of books…

Correspondence with Crick, Edelmann, Depak Chopra and others.

Milestones:

2004: Deaths of Thomas Gunn, Susan Sontag and Frances Crick.

73-82 (2006–2015): Visions, p. 623 =>TBD

[Sacks learns he has melanoma, and gradually loses vision in his right eye; he discusses the phenomenon of the filling-in of his scotoma with neurologist correspondents. During this period he finishes and publishes three books, and meets and begins his relationship with Billy Hayes.]

Sacks learns he has melanoma, and informs his correspondents; it is considered unlikely for it to metastasize. He has various radiation and laser treatments that increasing compromise vision in his right eye. In one letter he comments (not for the last time) on David Hume’s autobiography, My Own Life, and his calm reflections on his life and approaching death.

In spring 2006 he travels to Peru, and while there chews coca leaves, and reports on the visual imagery he sees when he closed his eyes — geometric patterns, lattices, and so on, as well as rapidly-changing scenes and images of faces. At this time he is writing Musicophilia, and mentions it in letters to various musically-inclined or -interested correspondents.

In 2007 he is experiencing a scotoma as a consequence of a re-growth of his melanoma, and discusses of the phenomena related to the ‘filling-in’ of the “intensely black irregular ink-spot.” He reports that if he is looking at something colored, the scotoma will change on to match the hue and brightness of what is in his visual field, and a similar although slower phenomena involving the filling-in of textures from the periphery in: “like ice crystalizing at the edge of a pond in winter, and then moves into the center.” And he reports that if he looks at a page of prints, after about 15 seconds the scotoma will fill in with psuedoprint that he can not actually read. He compares his internal pattern-matching to a cephalopod or flounder.

There is an interesting note on a blind woman — a musical savant — who can read braille, but only with her right index finger; she cannot read it with other fingers.

In 2007 Sacks is appointed to a chair in clinical neurology and psychology at Columbia, as well as a position as “Visiting Artist.” He seems pleased, but is not clear on what it will mean. We hear no more about this in the letters.

In 2008 Sacks has his first correspondence (to my knowledge) with Billy Hayes, his future partner. A few weeks later they meet in person for a meal, during Hayes’ visit to New York. Sacks drafts a letter to him afterwards, in reaction to some essays, and expresses condolences to Hayes for the loss of his partner, adding that, however, he cannot really feel what Billy and Peter had, “as I have never had … any ‘relationships’ at all.” Also, at this time, corresponding with a cousin, Sacks remarks that he loves Aumann’s description of how meaningful the Sabbath was to him, though he comments that in his family the practice was attenuated and that leaves him feeling wistful — but later, I think in 2015, Sacks will produce his own essay on the Sabbath that suggests he did find it deeply meaningful.

Correspondence with Bjork, Gwande, Edelman, Horovitz, Ramachandran

Milestones:

2007: Musicophilia published.

2008: First encounters with Billy Hayes

2010: The Mind’s Eye published.

2012: By this time Sacks is in a relationship with Billy Hayes.

2012: Hallucinations published.

2014: Friend from childhood Eric Korn dies.

2014: Gerard Edelman dies.

82 (2015): Gratitude, p. 675

[Over Christmas of 2014 he begins to feel ill and discovers that his melanoma has metastasized. He, and those who support him, make a plan to finish and publish as much of his work as possible. He says, in many letters, farewell to his many of his regular correspondents.]

Over Christmas of 2014 he begins to feel ill and discovers that his melanoma has metastasized. He, and those who support him, make a plan to finish and publish as much of his work as possible. He also makes a list of priorities that include ‘have fun, even be silly.’ 2015 would see the publication of On the Move, his coming out as a gay man, and nine essays in the NYT, New Yorker and New York Review of Books.

Sacks died at home on August 30, 2015.

Correspondence with Brunner, Gwande, Horovitz, Ramachandran, Lane.

Milestones:

2015: On the Move published.

2015: Gratitude posthumously? published.

2017: The River of Consciousness posthumously published.

2017: Everything in Its Place posthumously published.

Timeline / Milestones

1962: Moves to UCLA for Residency under August Rose.

1963-5: First professional success with research on hereditary myoclonus.

1965: First passionate love affair.

196x: Moves to NYC for plumb job at Einstein.

1966: Begins psychotherapy with Shengold.

1966: Sacks says a 20-year period of darkness comes to an end

196x: Encounters Migraine patients.

1970: Migraine published.

197x: Encounters Parkinson’s patients & uses L-Dopa on them.

1972: Fired from position at Beth Abrams.

1972: Mother dies.

1973: W. D. Auden dies.

1973: Awakenings published.

1974: Accusations of abuse at Beth Abrams.

1974: Sacks’ Norwegian leg accident.

First encounters people with Tourettes.

1977: Luria dies.

1979: Aunt Len dies.

198x: Some of his clinical accounts published in London Review of Books.

1984: A Leg to Stand On published.

1985: Kate Edgar becomes his assistant.

1983: Develops interest in deafness.

1985: Hat published. `

198x: Meets Steven Wiltshire, autistic artist.

1989: Seeing Voices published.

1990: The movie Awakenings is released.

1990: Father dies.

1995: An Anthropologist on Mars published.

1997: Island of the Colorblind published.

2000: Oaxaca trip.

2001: Uncle Tungsten published.

2002: Oaxaca Journal Published.

2002: Stephan Jay Gould dies.

2004: Deaths of Thomas Gunn, Susan Sontag and Frances Crick.

2007: Musicophilia published.

2008: First encounters with Billy Hayes

2010: The Mind’s Eye published.

2012: By this time Sacks is in a relationship with Billy Hayes.

2012: Hallucinations published.

2014: Friend from childhood Eric Korn dies.

2014: Gerard Edelman dies.

2015: On the Move published.

2015: Gratitude posthumously? published.

2017: The River of Consciousness posthumously published.

2017: Everything in Its Place posthumously published.

# # #

Views: 5