TBD

Views: 0

TBD

Views: 0

TBD

Views: 0

*The Catalyst: RNA and the Quest to Unlock Life’s Deepest Secrets, Thomas R. Cech, 2024.

Reading this with ‘the 26-minute book club in the Spring of 2025.

Nothing here yet.

Continue reading The Catalyst: RNA…*, Thomas CechViews: 1

A new SF novel by John Scalzi. The premise is that all of a sudden, with no warning or explanation, the moon turns into cheese. This has various ramifications, and the novel — which hasn’t much of a plot — is how various people react to this event, and its consequences.

I did not care for it. In fact, it is by far my least favorite Scalzi. I will be surprised if many people do, though of course Red Shirts won a Hugo even though I didn’t like it.

Views: 0

* The Left Hand of Darkness*, Ursula Le Guin, 1969. 50th Anniversary Edition.

w/EC-SF-bookclub: I am trying out this online book club run by the delightful musician-science-literary nerd Elle Cordova. You can find out about the club here, as well as back her many creative activities.

I am happy to have re-read this, after, I would guess, about five decades. I did not remember a lot about it, and the heart of what I remembered was wrong: I had remembered Genly Ai and Estraven having become lovers, if somewhat unwillingly driven to it by the pressures of Keemer and isolation. But they did not, though they did achieve a certain degree of understanding through forced intimacy. I did recall, of course, the hermaphroditism and short period of sexual dimorphism for a few days every month, and I recalled, but with few specifics, that it was clear that it changed how the culture worked.

Continue reading The Left Hand of Darkness*, Ursula Le GuinViews: 5

When I was a Child I Read Books, Marilynne Robinson, 2012. This is book #17 in the Essay Project, a series of reading I am doing with CT. It marks a return to literary essays after an epistolary detour into the letters of Olive Sacks, and only a temporary return as we have plans to finish the rest of Sacks’ work…

I must say, having just read the Preface and the first essay, I am beginning with a rather unfavorable impression. However, I will hope that her initial writing, which seems to me to quite polemical, will give way to more measured and approachable topics.

Later: After the discussing the first three essays, my reading partner and I decided that we would try to cherry-pick the essays, to see if we could find material we liked better. I proposed we read the title essay, and CT, after skimming the rest of the book, proposed we also read the final two. These are discussed below, but the bottom line is that while I can say that I enjoyed the title essay, the other two did not really grab me. I think, unless CT had a far different experience, we will stop after our next discussion, having read six of the ten essays.

Continue reading EP #17: When I was a Child…, Marilynne RobinsonViews: 10

The Disordered Mind: What Unusual Brains Tell us about Ourselves, Eric R. Kandel, 2018.

Kandel is an eminent neuroscientist, known for his work on the low-level mechanisms of learning and memory as demonstrated in Aplysia. He’s won a host of prizes, including the Nobel for this work. Interestingly, as an undergraduate he majored in humanities, and afterwards became a psychiatrist, before migrating into neuroscience. Now in his 90’s, he is writing about larger themes, and addressing himself to more general audiences.

Continue reading The Disordered Mind…, Eric R. KandelViews: 6

March 2025

I only discovered G. K. Chesterton a few years ago, through his essays which are generally excellent, and some which I would call brilliant. More recently I’ve dipped into his fiction. The Man Who was Thursday was superb, both surreal and funny, and laden with the striking descriptions — of landscapes, settings, people — of which Chesterton is a master. After that, just last month, I tried a second piece of fiction, The Napoleon of Notting Hill. I wrote a brief review of that, and, as I said, I did not care for that at all — it was clearly produced by the same author, but there the surreal became simply absurd, and the humor farce. Suspension of disbelief failed.

Still, having liked so much of his writing, and having found so little recent fiction satisfying, I wanted to try again, and so turned to his Father Brown stories about a Priest-Detective. The friend who had initially brought GKC to my attention recommended the story, The Blue Cross, as his favorite, and sent me a link to this volume on Project Guttenberg. The Blue Cross was indeed excellent, and so I proceeded through the rest of the volume.

Continue reading The Innocence of Father Brown, G. K. ChestertonViews: 2

A couple of years ago I read Chesterton’s The Man who was Thursday. I love it. The writing was beautiful in parts, and the story a blend of the absurd and surreal — it was funny, although I did catch on to what was happening pretty quickly. But still, it was quite delightful, and that was not dampened by the Chestertonian moral/religious overlay.

All that is to say that I picked up The Napoleon of Notting Hill with anticipation. Written circa 1903, the story was set in a future London — 1984 — where almost nothing had changed in terms of class, society or technology, with the exception that instead of having a hereditary monarchy, a monarch was selected at random. The story is about the selection of a new monarch who is deeply unserious, and for his own amusement decrees that the various neighborhoods of London should function as independent nations, with their own heraldry and uniformed guards (which the new King designed), and their own traditions and customs. All this is intended to restore some of the ‘romance’ of medieval times, and, to the King’s delight, soon results in armed battles between the neighborhoods — Notting Hill, in a surprise, becoming ascendant.

Anyway, that’s the starting point of the book, but I have to say it didn’t engage me much. Whereas ‘Thursday’ was funny and surreal, this was absurd and unbelievable. It took about 3/4 of the book (it’s short) for me to become at all engaged, and then it was more a matter of curiosity about how Chesterton would wrap it up, rather than caring about the characters or story. Towards the end Chesterton does make a case for his preference for romance and semi-feudal systems vis a vis modernity, but it was mainly interesting as reinforcing my understanding of Chesterton’s view of the world.

Too bad. …But I do intend to give a couple of his ‘Father Brown’ books — about his priest-detective, a try.

Views: 4

January 2025

I am told this is a classic papper. Here are some notes / excerpts:

Views: 0

January 2025

I picked up this book, probably about a year ago at the recommendation of Dan Russell. In terms of single-author collections, I’ve liked this more than anything I’ve read in years, perhaps with the exception of Loren Eisley’s essays. Regardless, Macdonald is a superb writer, and in particular her descriptions of the natural world are remarkable. I intend to seek out her other books.

I like, as well, her view of what literature ought to do:

What science does is what I would like more literature to do too: show us that we are living in an exquisitely complicated world that is not all about us. — Helen Macdonald, Vesper Flights. p. ix

This essay describes nests. She begins with her feelings about nests develop when she was a child, and encountered them in her yard. She then goes into the present, and reflects more on this than their meanings.

This essay describes an encounter with a boar. She reflects both on the boar, and more in general on animals in particular, and how the conception of an animal differs from the reality of the animal

Then it happens: a short, collapsing moment as sixty or seventy yards away something walks fast between the trees, and then the boar. The boar. The boar.

– Vesper Flights, Helen Macdonald, p 11.

A great bit of writing. The “short, collapsing moment.” The uncertainty about distance — “sixty or seventy yards” — and what she is seeing — “something.” The revelation: “and then the boar.” And the repetition: “The boar. The boar.“

A very nice short piece about an encounter with autistic boy, who is visiting her flat with his parents. In particular he connects with her bird and the bird with him.

“Field guides made possible the joy of encountering a thing I already knew but had never seen.”

An essay on the place where she grew up. A bit nostalgic, but it was unusual, and had interesting reflections, so I found it worth reading. Some very nice writing:

I could lie awake in the small hours and hear a single motorbike speeding west or east: a long, yawning burr that dopplered into memory and replayed itself in dreams.

— ibid. p 12

My eyes catch on the place where the zoetrope flicker of pines behind the fence gives way to a patch of sky with the black peak of a redwood tree against it and the cradled mathematical branches of a monkey puzzle, and my head blooms with an apprehension of lost space,

— Ibid. p 13

About watching migrating birds at night from the top of the Empire State Building. An interesting discussion of how birds migrate — the height and speeds at which they fly, and the way they navigate — and the problems that the lights and tall buildings of the city give them.

“Overhead a long wavering chevron of beating wings is inked across the darkening sky.“

Recounting the observation of large flocks of migrating cranes, and continuing to a discussion of the dynamics of swarms and murmurations. “Turns can propagate through a cloud of birds at speeds approaching 90 miles an hour…” This segues into a concluding comment on refugees, and a plea to regard them as individuals rather than masses.

An account of meeting a student who is a refugee and spending time in camps…

A great opening sentence:

There’s a window and the rattle of a taxi and grapes on the table, black ones, sweet ones, and the taxi is also black and there’s a woman inside it, a charity worker who befriended you when you were in detention, and she’s leaning to pay the driver and through the dust and bloom of the glass I see you standing on the pavement next to the open taxi door and your back is turned towards me so all I can see are your shoulders hunched in a blue denim jacket.

— The Student’s Tale, Vesper Flight, Kate Macdonald, p. 53

I think this is a marvelous stream-of-consciousness sentence, with the writers attention shifting from taxi to grapes to taxi to the woman and then to the student whose shoulders are hunched. The second person is also very effective.

About the mating flights of ants, and the birds that prey upon them. Also reflects on the power of scientific understanding to enhance the beauty of things, rather than detract: “…it’s things I’ve learned from scientific books and papers that are making what I’m watching almost unbearably moving.”

A red kite joins the flock, drifting and tilting through it on paper-cut wings stamped black against the sky.

[…]

The hitching curves of the gulls in a vault of sky crossed with thousands of different flightlines, warm airspace tense with predatory intent and the tiny hopes of each rising ant.

— Helen Macdonald, Vesper Flights, p. 63

Discusses her experiences with migraines. The writing is beautiful and ranges from describing the onset and symptoms of her migraine, to the way in which she has come to live with them. Ends with a partial analogy to earth undergoing climate change…

I was busily signing books when a spray of sparks, an array of livid and prickling phosphenes like shorting fairy lights, spread downwards from the upper right-hand corner of my vision until I could barely see through them.

—Helen Macdonald, Vesper Flights, p. 66

On mushroom hunting: “It is raining hard, and the forest air is sweet and winey with decay.“

The air is damp and dark in here. Taut lines of spider silk are slung between their flaking trunks; I can feel them snapping across my chest. Fat garden spiders drop from my coat on to the thick carpet of pine needles below.

—Helen Macdonald, Vesper Flights, p. 80

I like feeling the snapping, and the spiders dropping from her coat to the forest floor. It animates the scene, and tells us she is moving through it.

Beginning with her custom of walking in the woods every New Year’s day, she reflects on the things that are distinctive about forests in winter. From the revelation of the landscape, to the bark textures and angled branches of leafless trees, to the sometimes transitory life that becomes evident. Winter woods, she suggests, are full of potential:

So often we think of mindfulness, of existing purely in the present moment, as a spiritual goal. But winter woods teach me something else: the importance of thinking about history. They are able to show you the last five hours, the last five days, the last five centuries, all at once. They’re wood and soil and rotting leaves, the crystal fur of hoarfrost and the melting of overnight snow, but they are also places of different interpolated timeframes. In them, potentiality crackles in the winter air.

—ibid., p. 85

On viewing a solar eclipse. The phenomenology of the event, but also the deep, irrational, fundamental, emotional impact. The essay is reminiscent of Joan Didion’s essay, and in particular the way in which the fading daylight alters the colors in ways that cast the landscape in an alien light. It ends, beautifully, with a description of the light returning, and the emotions that brings.

A description of a trip with an astrobiologist to study extremophiles at very high altitudes in the Andes. Some beautiful descriptions of desolate and unworldly environments.

A description of the phenomenon of boxing hares, their place in English thought and mythology, and their decline due to environmental change.

A very short essay description her glimpse of a hound that was trying to catch up to the pack during a fox hunt.

About the English tradition of “Swan Upping,” and her experience observing the activity; all interladen with reflections on the role of tradition and its uneasy releationship to Brexit, which had recently occurred.

Discusses her changing feelings about deer, from initially wishing to known nothing about them and valuing them as a source of surprise and delight, to a desire to understand them. She says it better, though:

Deer occupy a unique place in my personal pantheon of animals. There are many creatures I know very little about, but the difference with deer is that I’ve never had any desire to find out more. They’re like a distant country I’ve never wanted to visit. I know the names of different deer species, and can identify the commonest ones by sight, but I’ve always resisted the almost negligible effort it would take to discover when they give birth, how they grow and shed their antlers, what they eat, where and how they live. Standing on the bridge I’m wondering why that is.

– Helen Macdonald, Vesper Flights, p. 141

As the title suggests, much of the essay is about deer-vehicle collisions; and also about how people react to them, in the moment, and, sometimes in cruel ways, on the internet. It is a complex essay. It doesn’t really speak to me, but there are a lot of great turns of phrase and passages.

Here is how the essay begins:

The deer drift in and out of the trees like breathing. They appear unexpectedly delicate and cold, as if chill air is pouring from them to the ground to pool into the mist that half obscures their legs and turning flanks. They aren’t tame: I can’t get closer than a hundred yards before they slip into the gloom.

– Helen Macdonald, Vesper Flights, p. 140

And here is a passage I admire for the way it highlights the incongruity of the two worlds: nature and the highway. It moves from the forest, to the road, to the forest, to the road, to her standing, embodied, on the bridge.

For a while the road doesn’t seem real. Then it does, almost violently so, and at that moment the bridge and the woods behind me do not. I can’t hold both in the same world at once. Deer and forest, mist, speed, a drift of wet leaves, white noise, scrap-metal trucks, a convoy of eighteen-wheelers, beads of water on the toes of my boots and the scald of my hands on the cold metal rail.

– Helen Macdonald, Vesper Flights, p. 141

She is watching birds — falcons — in an abandoned industrial plant in Dublin. The essay discusses falcons, and how they have adapted to living in cities and their infrastructures. Moves from their behavior and natural history, to the ways in which people have viewed them, to their change in habitat given the ‘advance’ of civilization. Ends with a reflection on the brevity of life, and a note of hope.

The essay that gives the collection a title. Begins with her finding a dead Swift and not knowing what to do with it. Segues into a description of Swifts and how they are somewhat “magical” — “the closest things to aliens on earth.” After describing their natural history, describes the phenonmenon of “vesper flights,” where they gather in the evening and fly up to 8,000 feet. She describes how this behavior was discovered, and goes through the history of this behavior being observed and understood. Interleaved with this is her accounts of how, as a small child, she sought comfort in the evening (her own private vespers) by imagining herself as embedded in layers of the earth below her and the atmosphere above her. This comes together as we learn that vesper flights, for Swifts, help them take account of where they are and the oncoming weather conditions, and as Macdonald reflects on ways in which she (we) can adopt practices that enable us to locate ourselves and think about what comes next.

A very nice, short essay about her annual practice of going to see glowworms in a quarry.

About her efforts to observe Oriels at the single place in Britain where they can still be found. Over time, their habitat is degraded, and at last there is only one… but, at the last moment, she is able to get a glimpse of it. She has a lovely sentence where she describes the song (or a song) or the oriel: “Wo-de-wal-e, wo-de-wal-e, a phrase like the curl of the cut ends of a gilded banner furling over the page of an illuminated manuscript.“

In this essay, she excels at capturing the fragmentary, mosaical nature of perception.

…what I saw became something like looking into a Magic Eye picture. Here was a circle, and in it a thousand angles of stalk and leaf and scraps of shade at various distances, and every straight stalk or branch was alternately obscured and revealed as the wind blew. I began to feel a little seasick watching this chaos, but then, as magically as a stereogram suddenly reveals a not-very-accurate 3D dinosaur, the muddy patch just off centre resolved itself into the nest.

[…]

Finally, I saw my oriole. A bright, golden male. It was a complex joy, because I saw him only in stamped-out sections, small jigsaw pieces of a bird, but moving ones, animated mutoscope views. A flick of wings, a scrap of tail, then another glimpse – this time, just his head alone – through a screen of leaves. I was transfixed. I had not expected the joyous, extravagant way this oriole leapt into the air between feeds, the enormously decisive movements, always, and the little dots like stars that flared along the edge of his spread-wide tail.

– Helen Macdonald, Vesper Flights, p. 177 & 179

About swans, beginning with an odd experience she had with one approaching her, and sitting beside her, in a moment of grief.

About a visit to a nature preserve with her young niece, and her niece’s puzzlement about why there were so many animals here — ‘did they bring them from a zoo?’ Reflections on the shift from a time when nature and animals were all around us, to the present, when they are mostly found in special preserves.

A short essay describing a thunderstorm, and also reflecting on storms as metaphors, in particular, in this essay, for the onset of Brexit.

Begins with getting a passport replaced at the last minute, and then moves to how birds were seen during war time, and the rise and evolution of the notion of birdwatching.

On cuckoos, how people perceive them, and in particular a rather eccentric British intelligence agent — Maxwell Knight — who raised a cuckoo. Didn’t grab me, but others might well find it a fascinating tale.

About tracking migrating birds. Makes this interesting point:

Projects like this give us imaginative access to the lives of wild creatures, but they cannot capture the real animals’ complex, halting paths. Instead they let us watch virtual animals moving across a world of eternal daylight built of a patchwork of layered satellite and aerial imagery, a flattened, static landscape free of happenstance. There are no icy winds over high mountain passes here, no heavy rains, soaring hawks, ripening crops or recent droughts.

– Helen Macdonald, Vesper Flights, p. 217

About destroying diseased trees, beginning with elms with Dutch Elm disease in her childhood, and ending with ash trees and the emerald ash borer.

About feeding animals. Starts with a nice anecdote about an elderly woman who put out corn to attract badgers at night. Continues into the practice of feeding animals, and makes the interesting point that there are some animals it is socially acceptable to feed, and others — foxes, rats, pigeons — that it is not.

This short essay begins with her decorating a Christmas tree, and sprucing up its decorations with berries from outside, but feeling slightly guilty because berries exist as food for birds. Segues into natural history of both birds and berries.

A great bit of description: “…like a gravity stricken whirlwind, a pack of fat birds swirled down from the blank sky…“

About the return of hawfinches to Britain, the excitement it engenders, and the ways in which their behavior seems to be changing vis a vis what habitat they prefer. Also touches on the blurring of natural history and national identity.

About the practice of capturing and keeping birds, which in England is mostly done by the working classes, and which is, it seems, looked down upon by others. She discusses the practice, how bird keepers feel about it and their birds, and the class differences and that this highlights. Interesting.

An interesting piece about hides (what we in the U.S. call “blinds”). It touches both on the aims and experience of watching animals from blinds, as well as the human experience within blinds.

A eulogy for a friend: a description of the her friend is interleaved with a night outing to see nightjars. A beautiful piece of writing.

The essay begins with a description of the outing, setting out while it is still light, but with the darkness coming:

As night falls, our senses stretch to meet it. A roebuck barks in the distance, small mammals rustle in the grass. The faintest tick of insects. The scratchy, resinous fragrance of heathland grows stronger, more insistent. As we pass clumps of viper’s bugloss we watch the oncoming night turn their leaves blacker, their purple petals bluer and more intense until they seem to glow. The paths become luminous trails through darkness. White moths spiral up from the ground, and a cockchafer zips past us, elytra raised, wings buzzing.

– Helen Macdonald, Vesper Flights, p. 255

After this, she makes the connection to her friend: “Soon all color will be gone. The thought is a hard one.” And then, after writing about him: “Now, watching the slow diminishment of sense and detail around me, I’m thinking of Stu and what is happening to him, thinking of his family, of what we face at the end of our lives’ long summers when the world parts from us, of how we all, one day, will walk into darkness.“

A somber essay, but ending with a note of, not hope, but acceptance. Stu says, “It’s OK. It’s OK. It’s not hard.”

It’s OK, he said. It’s not hard. Those are the words I am remembering as we walk onward, as the minutes pass, until night thickens completely and there is starlight and dust and the feel of sand underfoot. It’s so dark now I cannot see myself. But the song continues, and the air around us is full of invisible wings.

– Helen Macdonald, Vesper Flights, p. 259

An account of a visit to the house of a friend who rescues and rehabilitates swifts. It begins with her friend feeding nestlings, and ends with the release of a swift, and a haunting description of the swift’s transformation as it is about to take to the sky.

A brief, funny story about her, her dad, and pushing goats. Wouldn’t call it an essay though.

A curious essay centered around her experiences in her first job out of college, working on a falcon conservation-breeding farm. She describes what it was like — it sounded unpleasant to me, but she clearly got to do many things she loved and valued. She describes what led her to leave the farm, and does a good job of creating tension by naming two incidents, first “the dreadful incident with the ostrich,” and then “the cattle on the hill,” and describing each played out.

The ostrich incident — euthanasia of a horribly injured bird — was straightforward, if unpleasant. The “cattle on the hill” incident is quite strange: it involves her spending hours sneaking up on them, and then jumping up and scaring them into stampeding, though she does not know why.

At the end of the essay, though, she recounts an epiphany, and, for me, it resolves not just the ‘cattle on the hill’ incident, but the whole essay:

And then I thought of the day I stalked the steers on the hill and it resolved into perfect clarity. For I had seen myself as one of those steers, one of a feral and uncared-for herd enjoying life in the middle of nowhere, not thinking about what would happen in the future, and not much worried about it, but knowing deep down that one day I was headed for the abattoir. There would be no escaping the deep sea for the shore. And my stalking and shouting was not mindless. It had been an inchoate attempt to knock them out of their contented composure. It had been a warning to make them run the hell out of there, because the valley we were all in was dark and deep and could have no good end.

– Helen Macdonald, Vesper Flights, p. 282

An interesting essay with some nice passages in it, but it didn’t really resonate with me.

Discusses the author’s changing conceptions of and relationships to animals. She liked caring for them, as a child, but came to recognize that was about her feeling good about herself, rather than about the animals. As she grew older, she found that an intense focus on animals was a way to make herself disappear, to allow herself into a separate world that did not contain the difficulties she was faced with. Later, with respect to falconry, she speaks about how she learned that the other party in a relationship might see it very differently — a lesson she was slow to apply to humans. The “deepest lesson animals have taught me is how easily and unconsciously we see other lives as mirrors of our own.” And “None of us sees animals clearly. They are too full of the stories we have given them.“

Towards the end of the essay, speaking of a rook, she comments that now what she enjoys is not imagining that she can feel what the rook feels, know what it knows, but that it’s slow delight in knowing that she cannot.

As it passes overhead, the rook tilts its head to regard me briefly before flying on. And with that glance I feel a prickling in my skin that runs down my spine, my sense of place shifts, and the world is enlarged. The rook and I have shared no purpose. We noticed each other, is all. When I looked at the rook and the rook looked at me, I became a feature of its world as much as it became a feature of mine. Our separate lives coincided, and all my self-absorbed anxiety vanished in that one fugitive moment, when a bird in the sky on its way somewhere else sent a glance across the divide and stitched me back into a world where both of us have equal billing.

– Helen Macdonald, Vesper Flights, p. 299

Views: 7

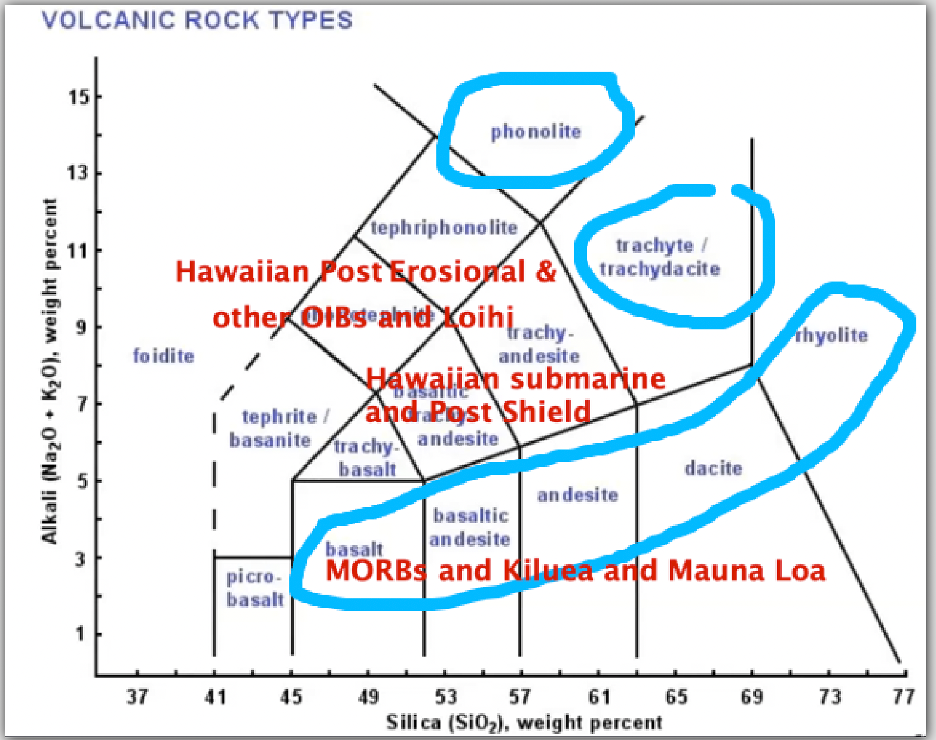

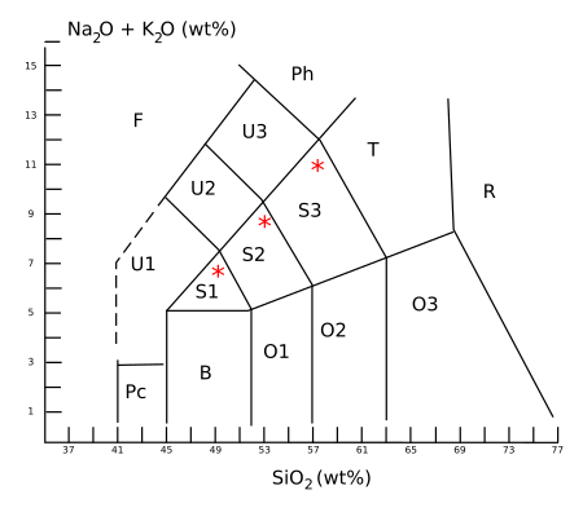

B (Basalt)—Use normative mineralogy to subdivide.

O1 (Basaltic andesite)

O2 (Andesite)

O3 (Dacite)

R (Rhyolite)

T (Trachyte or Trachydacite)—Use normative mineralogy to decide.

Ph (Phonolite)

S1 (Trachybasalt)—*Sodic and potassic variants are Hawaiite and Potassic Trachybasalt.

S2 (Basaltic trachyandesite)—*Sodic and potassic variants are Mugearite and Shoshonite.

S3 (Trachyandesite—*Sodic and potassic variants are Benmoreite and Latite.

Pc (Picrobasalt)

U1 (Basanite or Tephrite)—Use normative mineralogy to decide.

U2 (Phonotephrite)

U3 (Tephriphonolite)

F (Foidite)—When possible, classify/name according to the dominant feldspathoid. Melilitites also plot in this area and can be distinguished by additional chemical criteria.

(*)Sodic as used above means that Na2O – 2 is greater than K2O, and potassic that Na2O – 2 is less than K2O. Yet other names have been applied to rocks particularly rich in either sodium or potassium—as are ultrapotassic igneous rocks.

Palagonite is an alteration product formed from basaltic glass (tachylite); concentric bands of it often surround kernels of unaltered tachylite, and are so soft that they are easily cut with a knife. In the palagonite the minerals are also decomposed and are represented only by pseudomorphs.

Palagonite soil is a light yellow-orange dust, comprising a mixture of particles ranging down to sub-micrometer sizes, usually found mixed with larger fragments of lava. The color is indicative of the presence of iron in the +3 oxidation state, embedded in an amorphous matrix.

Palagonite tuff is a tuff composed of sideromelane fragments and coarser pieces of basaltic rock, embedded in a palagonite matrix. A composite of sideromelane aggregate in palagonite matrix is called hyaloclastite.

Phreatomagmatic. Palagonite can be formed from the interaction between water and basalt melt. The water flashes to steam on contact with the hot lava and the small fragments of lava react with the steam to form the light-colored palagonite tuff cones common in areas of basaltic eruptions in contact with water.

Weathering. Palagonite can also be formed by a slower weathering of lava into palagonite, resulting in a thin, yellow-orange rind on the surface of the rock. The process of conversion of lava to palagonite is called palagonitization.

Tachylite (from ταχύς, meaning “swift”) is a form of basaltic volcanic glass formed by the rapid cooling of molten basalt. It is a type of mafic igneous rock that is decomposable by acids and readily fusible. The color is a black or dark-brown, and it has a greasy-looking, resinous luster. It is often vesicular and sometime spherulitic. Small pheoncrysts of feldspar or olivine are sometimes visible. Fresh tachylite glass often contains lozenge-shaped crystals of plagioclase feldspar and small prisms of augite and olivine, but all these minerals occur mainly as microlites or as skeletal growths with sharply-pointed corners or ramifying processes.

All tachylites weather easily and become red to brown as their iron oxidizes.

Three modes of occurrence characterize this rock. In all cases they are found under conditions which imply rapid cooling, but they are much less common than acid obsidians. (Alkaline rocks have a stronger tendency to crystallize (i.e. not form glass), in part because they are more liquid and the molecules have more freedom to arrange themselves in crystalline order.)

The fine scoria (aka cinders) thrown out by basaltic volcanoes are often spongy masses of tachylite with only a few larger crystals or phenocrysts imbedded in black glass. Basic pumices of this kind are exceedingly widespread on the bottom of the sea, either dispersed in the pelagic red clay and other deposits or forming layers coated with oxides of manganese precipitated on them from the sea water. These tachylite fragments, which are usually much decomposed by the oxidation and hydration of their ferrous compounds, have taken on a dark red color (scoria is from σκωρία, skōria, Greek for rust.); this altered basic glass is known as “palagonite.” [see above]

In the Hawaiian Islands volcanoes have poured out vast floods of black basalt, containing feldspar, augite, olivine, and iron ores in a black glassy base. They are highly liquid when discharged, and the rapid cooling that ensues on their emergence to the air prevents crystallization taking place completely. Many of them are spongy or vesicular, and their upper surfaces are often exceedingly rough and jagged, while at other times they assume rounded wave-like forms on solidification. Great caves are found where the crust has solidified and the liquid interior has subsequently flowed away, and stalactites and stalagmites of black tachylite adorn the roofs and floors. On section these growths show usually a central cavity enclosed by walls of dark brown glass in which skeletons and microliths of augite, olivine and feldspar lie embedded

A third mode of occurrence of tachylite is as margins and thin offshoots of dikes or sills of basalt and diabase. They are often only a fraction of an inch in thickness, resembling a thin layer of pitch or tar on the edge of a crystalline diabase dike, but veins several inches thick are sometimes found. In these situations tachylite is rarely vesicular, but often shows pronounced fluxion banding* accentuated by the presence of rows of spherulites that are visible as dark brown rounded spots. The spherulites have a distinct radiate structure and sometimes exhibit zones of varying color. The non-spherulitic glassy portion is sometimes perlitic, and these rocks are always brittle. Common crystals are olivine, augite and feldspar, with swarms of minute dusty black grains of magnetite. At the extreme edges the glass is often perfectly free from crystalline products, but it merges rapidly into the ordinary crystalline diabase, which in a very short distance may contain no vitreous base whatever. The spherulites may form the greater part of the mass, they may be a quarter of an inch in diameter and are occasionally much larger than this.

See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flow_banding

Flow banding is caused by friction of the viscous magma that is in contact with a solid rock interface, usually the wall rock to an intrusive chamber or the earth’s surface.

The friction and viscosity of the magma causes phenocrysts and xenoliths within the magma or lava to slow down near the interface and become trapped in a viscous layer. This forms laminar flow, which manifests as a banded, streaky appearance.

Flow banding also results from the process of fractional crystallization that occurs by convection if the crystals that are caught in the flow-banded margins are removed from the melt. This can change the composition of the melt in large intrusions, leading to differentiation.

From GPT:

Fluxion banding results from shear forces within a moving magma body. This can happen in several ways:

1. Differential Flow in Lava. As lava moves, its viscosity varies due to cooling and crystallization. The outer layers, which cool faster, may develop a plastic or solid crust, while the inner material remains fluid. This difference in viscosity causes layers of magma to stretch and deform, forming elongated bands.

2. Crystal Sorting and Alignment. “ As magma flows, mineral crystals within it may become aligned due to shear stress. This is common in silicic lavas like rhyolite and dacite, where feldspar and quartz can form parallel bands.

3. Magma Mixing and Compositional Banding. If two magmas of different compositions mix, they may not completely homogenize, leading to streaks of contrasting compositions that appear as bands.

4. Intrusive Settings. In some plutonic rocks, fluxion banding may form as a result of late-stage magmatic flow, where crystals and melts segregate due to convection or deformation.

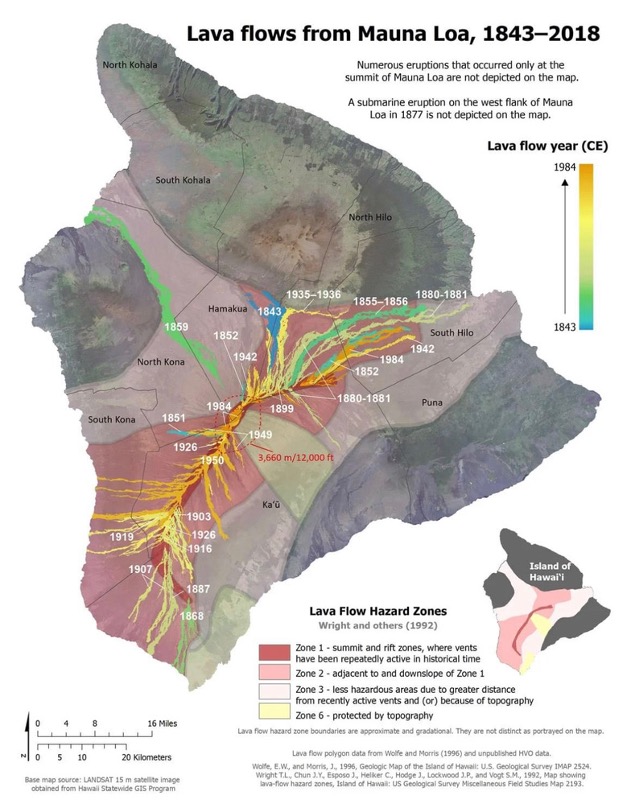

“The first two were the chemically evolved basalt of the initial fissures and the highly viscous andesite. Both are volumetrically minor sources that represent distinct pockets of old residual magma from Kīlauea’s east rift zone that evolved for more than 55 years, cooling and crystallizing at depth. The third and volumetrically more substantial source was less-evolved and hotter basalt of fissure 8. This source was similar in composition to the magma erupted at Kīlauea in the years before 2018 and was ultimately derived from the summit region. Draining and collapse of the summit by this voluminous eruption may have stirred up deeper, hotter parts of the summit magma system and sent mixed magma down the rift..”

Common minerals that crystallize from basaltic magma, ordered by the temperatures at which they typically form:

These minerals crystallize according to Bowen’s reaction series, where early-formed minerals (like olivine and pyroxene) are typically more magnesium- and iron-rich, while later-formed minerals (like plagioclase and spinel) are more silica-rich due to depletion of Mg and Fe.

TBD

.

Views: 7

December 2024 – April 2025

This is book # 16 in the no-longer-very-aptly named Essays Project. Though perhaps, having detoured into the wilds of Shakespeare, a tour of the letters of Sacks, who is a formidable essayist, is steering us back towards the main track. Of course, letters are not essays, but their relative brevity and personal cast, as well as the wide-ranging nature of Sack’s epistles, give them a familial resemblance.

The book is edited by Kate Edgar, Sacks’ assistant and editor of several decades; she also contributes a brief preface which offers her perspective on Sacks’ compulsive writing process. Alas for her brevity; I believe she could offer a lot of insight on Sacks. But perhaps his letters will serve. Onward!

Sacks loved correspondence. He felt one ought to reply to letters, immediately if possible. He corresponded with, literally, thousands of people, from school children to Nobel laureates. Sacks took pains to preserve his letters with carbon sets, drafts, or later, photocopies, though by no means does all his correspondence survive. But that part which does runs to about 200,000 pages, or about 70 bankers’ boxes.

Continue reading EP #16: Letters, Oliver SacksViews: 5

Cymbeline, angry that Imogen has wed Posthumos, banishes Posthumos and imprisons Imogen. Posthumos, in Rome, encounters Iachimo who sets out to to prove Imogen unfaithful. Queen requests a poison from her doctor, who gives her a fake one.

Continue reading CymbelineViews: 0

An interesting one. The first part is a tragedy; the second transforms it into a comedy. There are a lot of loose ends that are, mostly, tied up in the penultimate scene, in a series of disclosures to Autolycus, offered for unclear reasons.

I find Autolycus are curious character — a villain who morphs into a trickster. Paulina is, in my view, the hero of the story, though it is disappointing that she is married off at the end after she declares she is going to morn for her dead husband. Apparently marrying everyone off is de rigueur for a comedy.

Continue reading The Winter’s TaleViews: 0

Snow Crystals: A Case Study of Spontaneous Structure Formation, Kenneth Libbrecht, 2022

This is Libbrecht’s magnum opus, at least on snow; this goes deep into the science. …and I love that he has ordered the references by date, so you can see the history of the science leading up to Libbrecht’s work.

Notes still in progress…

Continue reading Snow Crystals, Kenneth LibbrechtViews: 10

See course notes for general material about Macbeth.

I continue (post Othello) not to be terribly keen on the tragedies, but liked this more than Othello.

Macbeth encounters three witches who prophesy that he will become Thain of Cawdor and King of Scotland, and that Banquo’s descendants will be kings as well. Shortly thereafter Duncan appoints Macbeth as Thain of Cawdor, but announces that he will appoint his own son as crown prince. Macbeth is ambitious, and toys with the idea of murdering King Duncan. However, he has reservations – Duncan is his lord, a kinsman, and a guest in his household. However, Lady Macbeth – who appears to have summoned evil spirits to give her resolve – shames Macbeth into going forward with the plot. So Macbeth murders Duncan, and pins the murders on drunken watchmen (whom Lady Macbeth has used a potion to put to sleep), and then has them killed, and blames Duncan’s sons for the murder.

Macbeth is crowned, but becomes increasingly unstable (as does Lady Macbeth( and paranoid). He seeks out the witches, who warn him to be wary of MacDuff, but assure him that no man borne of woman can kill him, and the he will not be defeated until Birnam Wood moves to Dunsinane Hill. After this, Macbeth goes on a bit of a killing spree, arranging the murder of his friend Banquo (to eliminate his descendants the witches said would inherit the throne – except Banquo’s son escapes) and the family of the nobleman Macduff. Plagued by ominous visions—such as Banquo’s ghost appearing at a royal banquet—Macbeth’s grip on power loosens.

Meanwhile, Macduff and Duncan’s heir, Malcolm, raise an army in England and return to overthrow the usurper. Macbeth tries to avoid fighting Malcolm, but upon Malcolm’s pronouncement that he will take Macbeth captive and parade him about, Macbeth fights, and is slain and beheaded. Order and justice is restored.

Views: 1

November 2024 – April 2025

* Why Machines Learn: The Elegant Math Behind Modern AI, Anil Ananthaswamy, 2024. (Ananthaswamy is a science journalist, not an AI person, as I initially assumed. That said, he’s quite good.)

As discussed below, this is not the sort of book I’d usually read — my interest stops at the level or algorithms, and understanding the underlying math just doesn’t grab me. This really is a book for people interested in the math. But I learned some interesting, mostly-meta things from it.

Views: 7

Four Billion Years and Counting: Canada’s Geological Heritage. Produced by the Canadian Federation of Earth Sciences, by seven editors and dozens of authors. 2014.

November-December, 2024.

I am reading this with CJS. It is a nice overview of regional geology, and it is nice that all the examples come from Canada, and at least some of the discussion is relevant to Minnesota Geology. The book is notable for its beautifully done pictures and diagrams.

Continue reading Four Billion Years and Counting…Views: 14

November 2024

Reading as part of the Fall 2024 Shakespeare course — see general notes for more.

Although its a famous play, and does indeed contain some striking things — particularly Iago’s manipulation of Othello, and also the use of the hankerchief as symbol of fidelity and betrayal – I was not that keen on this play. Give me some comedy, or at least a little more magic!

Othello, a famous general fighting for Venice, has just married Desdemona, to the dismay of her father. Othello is black, and an outsider, and knows little of the customs or society of Venice – but he is valued due to his military prowess, especially as the Turks seem about to attack. He has chosen the polished and bookish Cassio as his lieutenant, much to the distress and anger of Iago, who has spent his life in the field and believes he has earned the postion. Iago decides to get revenge, and aims to destroy Cassio and Desdemona and, through her, Othello.

After this, the play unfolds in a straightforward way. Iago subtly raises questions about Desdemona’s faithfulness – all the while pretending that he is reluctant to speak and is unsure of the truth of what he is saying – and in a famous scene transforms Othello’s trust of Desdemona into suspicion, suggesting that she is having an affair with Cassio. Iago is one of Shakespeare’s most famous villians – Coleridge referred to him as having “motiveless malignity.”

Othello wants visible proof, and here Desdemona’s hankerchief comes into play. It was her first gift from Othello, and it was woven by a fortune teller with magical properties. Iago secrets Desdemona’s hankerchief (which she had lost and Emilia found and given to Iago) in Cassio’s quarters. Cassio finds the hankerchief and gives it to the courtesian Bianca to copy – Othello watches this from a distance, and believes it proof of Desdemona’s infidelity. Othello orders Iago to kill Cassio, and Othello strangles Desdemona. When it is revealed that Desdemona was innocent, Othello kills himself.

Views: 0